Adult Acne Really Gets Under My Skin

I remember my introduction to puberty, my real introduction. It wasn’t a growth spurt, a voice change, or new body hair. It was a big. fat. zit. Right on the face. I was lucky, only getting a few zits here and there, but they still managed to kill my confidence. Unfortunately, it can be much, much worse for many people. Acne affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide and millions in the United States alone. Though most (85%) people experience acne in adolescence, nearly half of adults in their twenties have the condition. Beyond a simple zit here or there, acne can cause grease, lesions, and permanent scarring to the face and upper body. Acne can be graded based on the severity as mild, moderate, or severe. This can have serious negative impacts on mental health and quality of life. To really get under the skin of what’s going on with acne and what to do about it we first have to understand where and how it happens.

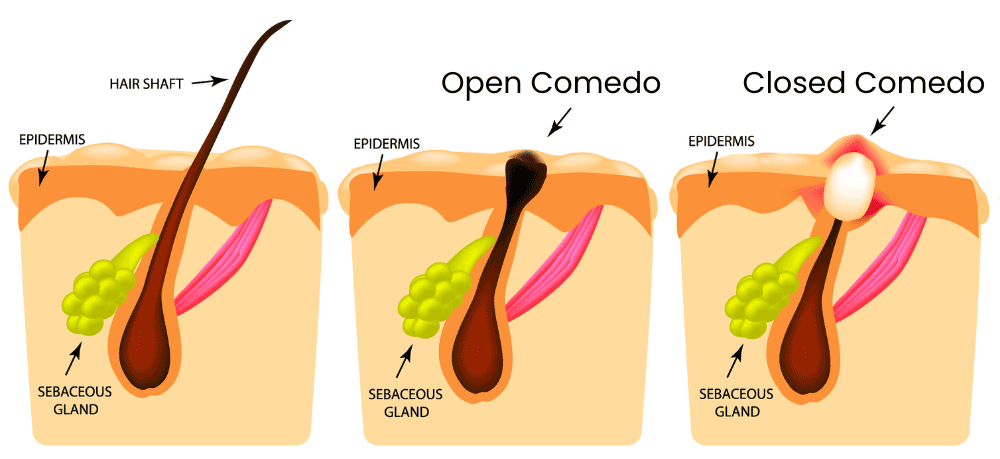

Acne arises in the sebaceous gland. Sebaceous comes from Latin and shares its root word with soap. These glands produce an oily fat called sebum that coats our hair and skin and helps keep them from drying out. Instead of being gross, they are super helpful. The gland itself is embedded in the skin with a hair follicle, where hair is made. Together, these make up a pilosebaceous unit (Latin for hair-grease). Along with producing oils, the sebaceous gland also has the ability to sense its surroundings. It detects and responds to changes on the skin and hormonal changes in the body. Unfortunately, they can be confused and cause acne.

There are many causes of acne, but they can be roughly divided into four main factors: increased sebum, obstruction of the pilosebaceous unit, colonization by a bacterium, and an inflammatory response.

Increased sebum is when too much of the oily, waxy fat is produced. This is usually called androgen-mediated sebogenesis, which gives a clue. The issue is an imbalance of hormones known as androgens. These are a type of steroid that can cause the sebaceous gland to produce too much sebum, which can clog the pilosebaceous unit.

This brings us to obstruction of the pilosebaceous unit. Most of the machinery of the pilosebaceous unit is located in the middle layer of skin, and it squeezes out of a small pore at the top. This pore can get clogged by sebum and hair components. A small clog is called a microcomedo. The micro– is there because the skin still looks and feels normal. If the buildup continues, there is swelling and we get a full comedo (plural comedones). This is the zit, a clogged pilosebaceous unit. Side note: the comedo can be fully covered (closed) or exposed to air (open). When covered, skin pigments are preserved and we get a whitehead. When open, oxygen causes discoloration and darkening of the sebum, leading to a blackhead.

But why does the buildup start? What’s causing this excess production? Surprisingly, the culprit has to do with the skin microbiome! This includes large amounts of (mostly helpful) bacteria that live on and in the top few layers of the skin. With acne, the little guy in question is named cutibacterium acnes, formerly called propionibacterium acnes. This bacteria is everywhere and lives happily without oxygen inside your pilosebaceous unit your whole life. It usually regulates the stability of the sebaceous gland. There are multiple strains of cutibacterium acnes (c. acnes), and some are worse than others. On the surfaces of the bacteria are proteins that vary by strain and conditions around the sebaceous gland. These can help it survive and can fight other bacteria. In some instances, these proteins can attach to the parts of the pilosebaceous unit that sense its environment. In acne-causing strains of c. acnes, the proteins activate receptors that regulate inflammatory responses. These strains are more likely to be dominant when the skin microbiome is out of whack and/or the pilosebaceous unit is producing too much sebum. The problem with c. acnes, then, isn’t the bacteria itself, but destructive strains and a skewed skin microbiome.

This brings us to the last factor contributing to acne: inflammation. Inflammation is the body’s response to dangerous invaders. It is responsive and quick but can have trouble learning from its mistakes. With acne, the inflammation system is activated by rogue c. acnes strains and attacks enemies that aren’t there. This results in the reddening and swelling typical of a zit.

So, what can be done about acne? With the enormous number of people who get acne and the very public nature, there are a lot of treatments with varying results. Skin cleansers have inconsistent data showing efficacy.

The first medical lines of defense are topical agents. Retinoids, derived from vitamin A, bind to skin cells and promote extra skin cell production, which helps clear sebaceous ducts and microcomedones. Benzoyl peroxide is cheap and effective, generating killer free radicals that enter the pilosebaceous unit and kill c. acnes indiscriminately. Topical antibiotics can be effective at combating rogue c. acnes, but improper or excessive use can create antibiotic resistance, an increasing problem with acne.

The second lines of defense are systemic agents that affect the whole body. These include medications that suppress androgens, oral antibiotics, and systemic retinoids. Since they are systemic, side effects are typically more severe than with topical treatments, but they can be used to treat moderate-to-severe acne. But what if there were another way? On the very verge of research is a c. acnes vaccine! An effective vaccine would target just the dangerous strains of the bacteria and would hopefully provide lasting protection. With luck, future generations can be introduced to puberty with parental embarrassment instead of acne!

Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

Listen to the article here:

References:

Barbieri, J. S., Wanat, K., & Seykora, J. (2014). Skin: basic structure and function. https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780123864574/pathobiology-of-human-disease

Das, S., & Reynolds, R. V. (2014). Recent advances in acne pathogenesis: implications for therapy. American journal of clinical dermatology, 15, 479-488. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40257-014-0099-z

Del Rosso, J. Q., & Kircik, L. (2024). The cutaneous effects of androgens and androgen-mediated sebum production and their pathophysiologic and therapeutic importance in acne vulgaris. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 35(1), 2298878. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09546634.2023.2298878

Dréno, B., Pécastaings, S., Corvec, S., Veraldi, S., Khammari, A., & Roques, C. (2018). Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 32, 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15043

Mayslich, C., Grange, P. A., Castela, M., Marcelin, A. G., Calvez, V., & Dupin, N. (2022). Characterization of a Cutibacterium acnes Camp Factor 1-Related Peptide as a New TLR-2 Modulator in In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models of Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(9), 5065. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijms23095065

Mayslich, C., Grange, P. A., & Dupin, N. (2021). Cutibacterium acnes as an opportunistic pathogen: An update of its virulence-associated factors. Microorganisms, 9(2), 303.