GRID VIEW

There are many ways to think of the human body. One of my favorites is that the body is like a donut. The inside of the donut is our entire body and everything that makes us what we are. The outside is our skin. The hole in the middle is made of our mouth, throat (esophagus), stomach, and intestines. The body treats the entirety of the digestive tract as the outside world. The intestines act like the skin; keeping most things out of the body and only letting specific molecules through. This has some important implications. The whole outside of the donut – including the throat and intestines – is covered in epithelial cells. These are tight cells that interact with the outside world. When these cells determine that they are touching something dangerous they signal to get rid of it immediately. This might feel like burning or itching on the skin, and may be something like diarrhea or vomiting in the digestive tract. These may feel crummy to us, but they are very useful in keeping us safe. The immune system is in charge of identifying and reacting to chemical and biological dangers. These can be harmful bacteria, worms, and things like splinters or some drugs. The immune system kicks into action, trying to kill or remove the dangerous particles without damaging body cells. This is a tricky dance. Antibodies will identify the dangerous particles or creatures and special B or T cells will widely sprinkle alarm particles, calling for reinforcements. What the body does next is determined by where the danger is found. In the gut – which the body treats as the dangerous outside world – the defenses are strong. One of the biggest guns we have is a cell called an eosinophil. These are very dangerous cells. They contain highly toxic particles and proteins that aggressively dunk in on invaders. They also signal to the intestines to contract and eject the contents. They only exist in specific parts of the body and are normally difficult to activate. Unfortunately, sometimes our body identifies otherwise safe items as dangerous. This is called allergies, and can be very annoying. Many of us suffer from seasonal allergies, but that doesn’t mean we should glaze over the dangers of allergic reactions. One difficult condition is eosinophilic esophagitis. Eosinophilic means it is caused by the dangerous eosinophil cells. Esophagitis refers to the fact that this happens in the esophagus, the throat. Eosinophils do not normally reside in the throat at all. The throat’s main job is to move food into the stomach, so it doesn’t need to detect danger. When eosinophils mistakenly reside in the throat, however, they can misidentify otherwise safe foods before the stomach gets a chance to digest them. This can result in the eosinophils damaging the throat. Eosinophilic esophagitis affects four in every thousand people, and can affect people of all ages. Most sufferers were diagnosed as children. In fact, it is one of the most common diagnoses for children who have trouble eating. It is chronic, or long lasting, and symptoms are debilitating. Sufferers experience inflammation of the throat, poor food intake, vomiting, and a poor appetite. Unfortunately there are few treatments available to fix this condition. The most effective has been reducing the diet of patients. This may consist of starting with a very strict diet and reincorporating food slowly to discover triggers. Scientists are actively looking at the underlying causes of why eosinophils are in the throat to begin with. Possible future treatments would likely stop eosinophils in the throat at a cellular or genetic level. The body may be a donut, but that doesn’t mean everything is tasty and fresh. If you are suffering from eosinophilic esophagitis or other conditions, call ENCORE Research Group and ask about studies you may qualify for. By Benton Lowey-Ball, BS Behavioral Neuroscience

Furuta, G. T., & Katzka, D. A. (2015). Eosinophilic esophagitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(17), 1640-1648. https://doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMra1502863 Janeway Jr, C. A., Travers, P., Walport, M., & Shlomchik, M. J. (2001). Effector mechanisms in allergic reactions. In Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. Garland Science. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27112/ Rothenberg, M. E. (2004). Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID). Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 113(1), 11-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.047 Zuo, L., & Rothenberg, M. E. (2007). Gastrointestinal eosinophilia. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America, 27(3), 443-455.https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.iac.2007.06.002

Listen to the article here:

What is EoE? What are the symptoms? How to get diagnosed. Current research on EoE.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic disease of the esophagus. Your esophagus is a muscular tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach. EoE is when white blood cells (called eosinophils) build up in your esophagus.

Some of the most common symptoms of EoE are:

Your doctor will most likely want you to have an endoscopy to diagnose EoE. An endoscopy is a procedure where an endoscope (a tube with a light and camera attached at the end) is inserted into the body to let your doctor look inside an organ. For an esophageal endoscopy, the endoscope is put in your mouth and down your throat to examine the esophagus. But don’t worry, you’re not awake for that part! Other ways you can be diagnosed are biopsies, blood tests, and an esophageal sponge.

Science continues to move forward for new treatments of eosinophilic esophagitis, and we are delighted to be involved in these cutting-edge research trials at some of our ENCORE Research Group locations. To learn more about participating in our cutting-edge clinical trials, call our main office today! (904)-730-0166

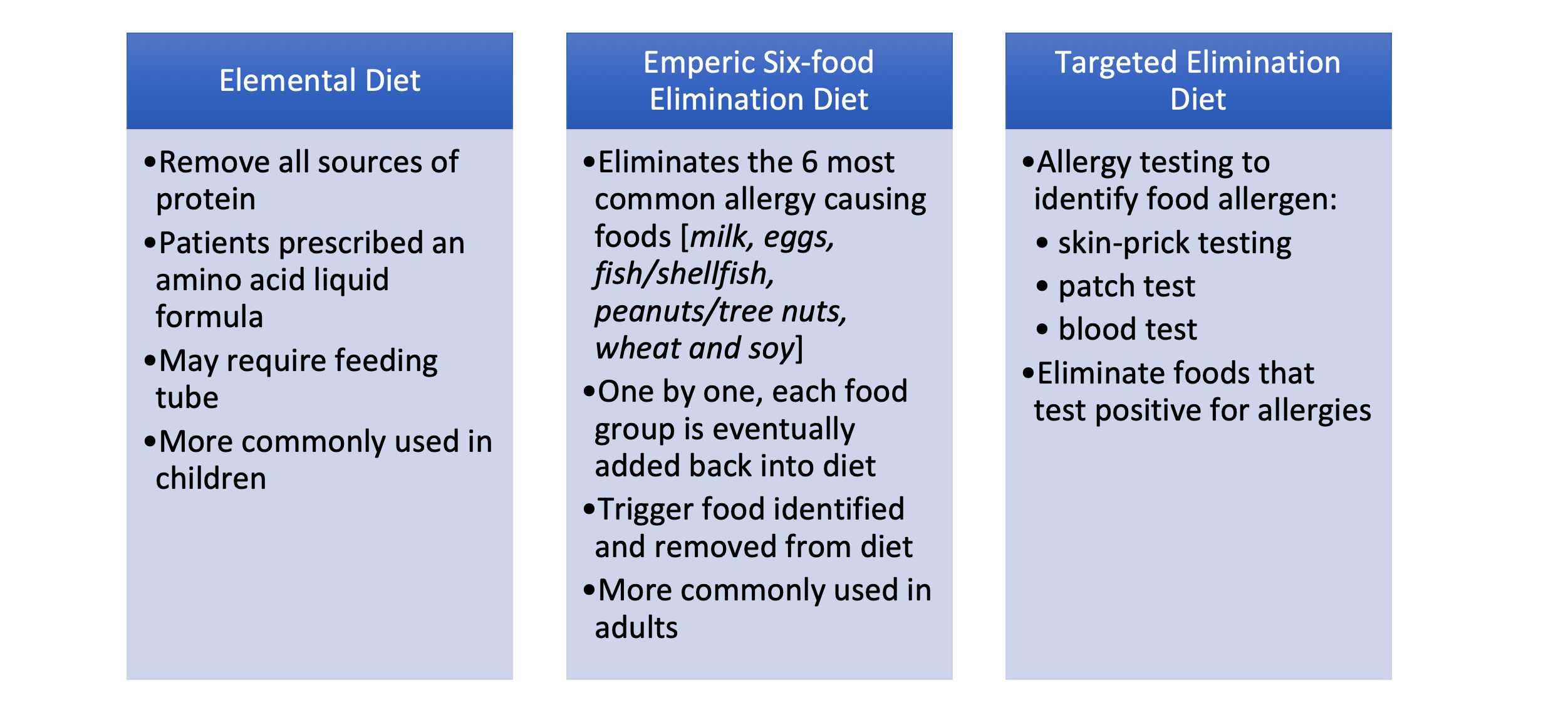

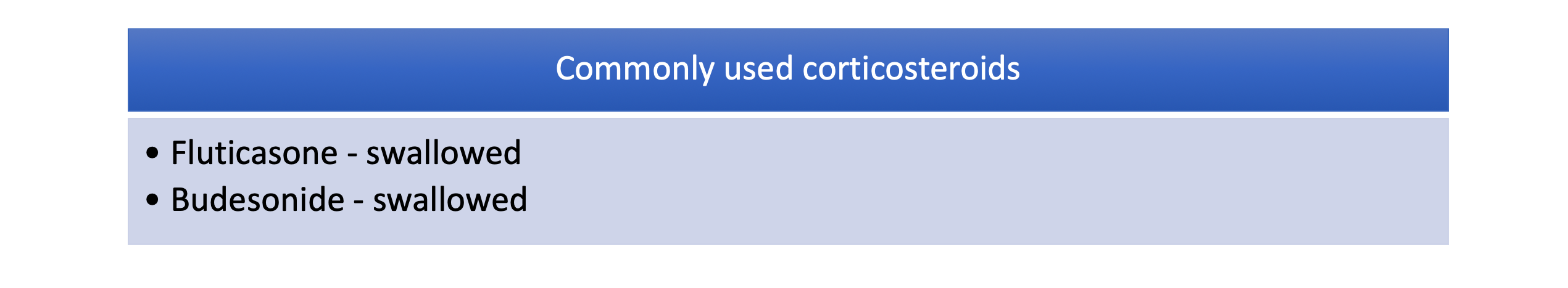

Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, immune-mediated disorder. It occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 people and affects people of all age groups, with males being affected more frequently. EOE is associated with food allergies or other allergens, causing eosinophils (type of white blood cell) to migrate from the bone marrow (via blood) and settle in the esophagus causing inflammation to the esophagus. No one knows exactly why EoE occurs. People with EoE tend to have allergic conditions such asthma, seasonal allergies, allergic rhinitis, and eczema. Symptoms of EoE: EoE symptoms can overlap with symptoms of a condition called gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Patients with EoE experience symptoms described as, If EoE is not controlled, the eosinophils will cause damage to the esophagus. Sometimes food that gets stuck in the esophagus (food impaction) may require emergency removal. How is EoE Diagnosed? If you have symptoms of EoE, your doctor will order a procedure called an endoscopy (EGD). An EGD is required to confirm the diagnosis and is performed by a specialist called a gastroenterologist. Patients are sedated for this procedure and a small flexible tube with a light and camera on the tip is inserted into the patient’s mouth. During the endoscopy, several biopsies of the esophagus will be taken and sent to the laboratory for analysis under a high-power microscope. EoE is confirmed when 15 or more eosinophils per high-power field are found (≥15 Eos/hpf). How is EoE Treated? Many patients with EoE are initially treated for GERD using a medication called a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). However, most EoE patients do no respond to anti-GERD treatment. Treatment with PPIs is given for a minimum of 8 weeks followed by a repeat EGD and biopsy. If the eosinophil count remains elevated (≥15/hpf), the diagnosis of EoE is confirmed and a different treatment is given. Patients with EoE are often referred to an allergy specialist for evaluation. Allergy testing can be done to identify which foods are triggering the EoE. Treatment for EoE usually includes dietary management and/or medication, or treatment on a clinical trial. If you have symptoms of EoE, it is important that you seek medical care and discuss your symptoms with your doctor. You can also learn more about EoE from advocacy organizations such as Apfed (apfed.org), or by joining an on-line patient communities such as Healtheo360 (healtheo360.com). Research is currently being conducted around the United States for this condition. Here at ENCORE Research Group we have 3 research sites with a new opportunity for people who have Eosinophilic Esophagitis. If you’re interested in learning more about this research, please contact your local research office below! Jacksonville: ENCORE Borland Groover Clinical Research 904-680-0872 Fleming Island Fleming Island Center for Clinical Research 904-621-0390 Inverness: Nature Coast Clinical Research 352-341-2100