GRID VIEW

When a looming deadline stresses me out, I often remember the classic advice to take a deep breath – but what if you can’t? This may be the case for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, also called COPD. COPD is a progressive lung disease that may feel like you are trying to breathe through a tiny cocktail straw. This difficulty in breathing is caused by the deterioration of the structure of the lungs. It affects around 10% of the global population and nearly 15% of Americans, resulting in approximately 150 thousand deaths per year in the US. COPD rates increase as socioeconomic status drops, meaning it is more prevalent among poorer individuals. COPD symptoms can range from mild to severe. Shortness of breath, cough, and excess phlegm are common. More severe COPD can result in hospitalization and death. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and chronic bronchitis both affect and are affected by COPD. Lifelong accumulation of damage to the lungs characterizes COPD, with risk factors including most things that affect lung health. Some risk factors can’t be helped, like genetics or lung development from childhood. Others are environmental, including air pollution and infections like tuberculosis or HIV. Several risks can be mitigated through lifestyle choices, the most important being smoking. Smoking directly puts destructive particles into your lungs, greatly increasing your chances of developing COPD. This includes cigarettes, but also vaping, and marijuana. Inactivity, a poor diet, and jobs that expose you to particulate matter, like stone dust and pesticides, also contribute. The final risk factor is time. Lung capacity peaks in your early 20s and damage to the lungs from the above causes accumulates over time. So how do these things cause damage, and what can we do about it?

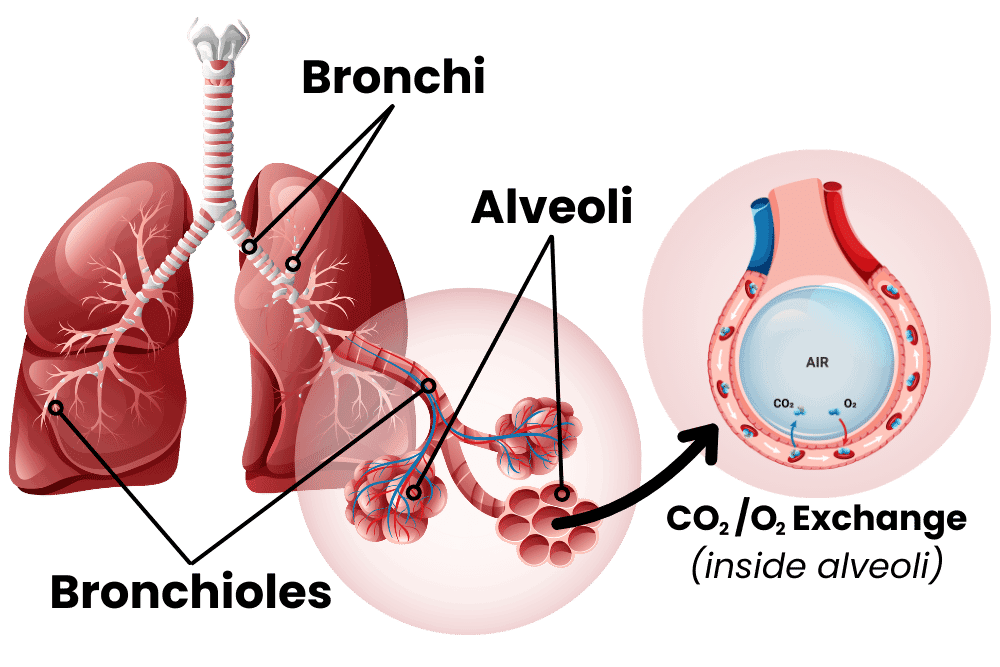

To understand COPD, let’s first inhale a little crash course on the lungs. I always see lungs drawn like they’re giant balloons, but they’re really more like sponges. The airway moves from the big throat to smaller and smaller fractal channels called bronchi and bronchioles until they reach the alveoli. These are teeny-tiny little balloons, and there are hundreds of millions of them in the lungs. These tiny sacs have thin walls and are the interface between air and blood, allowing for carbon dioxide to be exchanged for fresh oxygen. The tiny sacs provide a lot of surface area for this exchange to take place. Altogether, the inner surface of all the alveoli is called the lung parenchymal, and its surface area is close to the size of a tennis court! The lungs can’t expand on their own, so the smooth muscle of the lungs keeps bronchi and bronchioles from collapsing. When the lung is damaged over time, COPD may occur. This damage manifests in the airway, the alveoli, or both. The airway, made up of bronchi and bronchioles, can become inflamed, resulting in bronchitis (bronchi + itis, meaning inflammation of). The lungs have their own immune system, including a slimy mucus layer, but chronic insults to the lungs (like smoking for years and years) can degrade this system. With bronchitis, big and dangerous immune cells like macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes may enter the lungs. These cells are good at removing invaders but can cause damage to surrounding tissue through inflammation. When the damage lasts for years, this chronic inflammation can narrow the airways, degrade tissue, and cause a thickening or scarring of lung tissue called fibrosis. The end result of all of this is increased resistance from the airway: it’s harder for the lungs to draw in air. Emphysema occurs when the lung parenchymal is damaged. Alveoli are destroyed, some of them combine into larger holes, and functional surface area is reduced. This reduces the lungs’ capacity and elasticity, making them less able to deflate. The combined effects of bronchitis and emphysema lower lung function – you can’t exchange as much carbon dioxide for oxygen. So what can we do to fix COPD? The first step is to stop the damage. Smokers with COPD should stop immediately. Quitting smoking can be extremely hard, especially as many smokers started in their teens when the brain was still cementing lifelong habits. You should also improve other modifiable lifestyle risks; increase exercise, make sure your diet is healthy, and try to reduce exposure to air pollution. Doctors recommend lowering the risks of exacerbating infections by getting vaccines for flu, RSV, COVID, pneumonia, and Tdap. Beyond these measures, pharmacology can provide relief. Medical treatments are generally added in a stepwise, increasing fashion to control symptoms and to reduce exacerbations with a minimum of side effects. The major available medications are usually lumped into bronchodilators and antimuscarinic drugs. Bronchodilators do just what it sounds like they do, they dilate (expand) the bronchi and bronchioles. Beta2 agonists are the archetypal bronchodilators, they change the function of lung muscle and widen airways. They can be short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) or long-acting (LABA). Antimuscarinic drugs are similar. They act on muscarinic receptors in smooth muscle. These receptors regulate bronchodilation, mucus secretion, and inflammation. There are short and long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (SAMA and LAMAs). On top of these, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) may help reduce inflammation. LABA medications may increase the effectiveness of ICS inflammation reduction. When a single medication fails to control symptoms or stop complications, a dual medication of LABA + ICS or LABA + LAMA may be prescribed. Mounting evidence is also showing that a triple medication of LABA + LAMA + ICS may provide advanced relief when a dual medication isn’t sufficient. If these combination medications pan out, those with COPD may be able to finally breathe a sigh of relief. Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Adeloye, D., Chua, S., Lee, C., Basquill, C., Papana, A., Theodoratou, E., … & Global Health Epidemiology Reference Group (GHERG. (2015). Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: Systematic review and meta–analysis. Journal of global health, 5(2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4693508/ Alagha, K., Palot, A., Sofalvi, T., Pahus, L., Gouitaa, M., Tummino, C., … & Chanez, P. Íp(2014). Long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists for the treatment of chronic airway diseases. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease, 5(2), 85-98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3926345/ GOLD, 2023 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). (2023). 2023 Report: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://goldcopd.org Rabe, K. F., Martinez, F. J., Ferguson, G. T., Wang, C., Singh, D., Wedzicha, J. A., … & Dorinsky, P. (2020). Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(1), 35-48. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1916046 Suki, B., Stamenovic, D., & Hubmayr, R. (2011). Lung parenchymal mechanics. Comprehensive Physiology, 1(3), 1317. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3929318/ CDC & National Center for Health Statistics. (May 2, 2024). Leading causes of death. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

Listen to the article here:

Lung cancer is distressingly common. Worldwide, over 2 million people per year are diagnosed with lung cancer, including over 200,000 in the USA. It is more common in men than women. Lung cancer has many debilitating symptoms, including chest pain, voice changes, weight loss, discomfort, coughing blood, and death. Lung cancer is the highest cause of cancer death in men and the second highest in women, and the outlook gets worse the later in the disease you are diagnosed. So what causes lung cancer, how does it work, and is there anything we can do about it? Lung cancer has several different risk factors, including low socioeconomic status, HIV, and some lung diseases. According to the National Institute of Health, radiation from atomic bombs can also increase your risk, so avoid atomic bombs. None of these come even close to the explosive risk from smoking, however. Smoking causes lung cancer and increases your risk of developing lung cancer by 20 times versus people who have never smoked. Smoke contains a lot of chemicals. Some of these enter the cells that line the throat and lungs and damage the DNA. Unfortunately, the advent of filtered cigarettes encouraged people to inhale smoke more deeply and increased cancer rates. There are at least 15 genes implicated in the conversion of cells from normal to cancerous. Cigarette smoke, along with air pollution, other carcinogens, and random mutation, can change some of the DNA in these genes and make cells cancerous. Let’s take a quick second to review what cancer is. Cancer cells are cells that have mutated and act more like independent, single-celled organisms than part of your body. They grow and divide even when they aren’t supposed to, they don’t kill themselves when they outlive their usefulness, and they move around invading other parts of the body. Unlike most single-celled organisms, they are extremely difficult to kill. They are made out of our cells, so most medicines can’t distinguish them, they hide from the immune system, and they convince parts of the body to aid their unrestricted growth. Each of these is an individually unlikely mutation. Still, the damaging effects of carcinogens like cigarette smoke cause many rapid changes in the genes of the cell, increasing the possibility that cells will acquire the necessary mutations. As cells reproduce out of control, they are more likely to mutate and acquire the other necessary mutations to become cancerous. They act independently and take resources, space, and blood from healthy cells, crowding them out and destroying large body systems. Lung cancer is differentiated from other cancers in an obvious way; the cancerous cells originate in the lungs. Epithelial cells line the lungs and create a protective barrier against environmental hazards. When they are exposed to smoke and other carcinogens this can cause mutations. Medical professionals and researchers have long-differentiated subtypes of lung cancer based on the type of cell that has become cancerous. These are broadly defined as small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). SCLC is very aggressive. It makes up 15% of all cases and has a 5-year survival rate under 10%. This type of lung cancer responds well to chemotherapy but spreads rapidly and is difficult to treat when it has moved extensively. NSCLC makes up the rest of the cases, 85%. There are several subtypes, including squamous cell and large cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, the most common type. NSCLC has a multi-step process and can be caught early when cells are replicating or grouping together but are not yet cancerous. This type of lung cancer does not respond as well to chemotherapy. Surgery or surgery combined with chemotherapy is usually recommended. So what can we do about lung cancer? First and foremost, if you don’t already have lung cancer, make sure you STOP SMOKING. There are programs, medications, and support groups that may help. Non-smokers should also be aware of the risks and symptoms. Beyond that, early detection is critical. Cancer can be localized in only one organ, spread to the lymph nodes, and eventually spread throughout the body. When lung cancer is localized, 5-year survival rates are over 50%. When it has metastasized and spread to other locations, that survival rate drops below 5%. If you are at risk, inquire with your doctor about lung cancer screenings and be vigilant. If you currently have lung cancer, your doctor has the best information available for your specific case. Treatments include surgery and chemotherapy, along with radiation therapy, immunotherapy, laser therapy, stents, and experimental treatments. Though ENCORE Research Group sites do not currently have any lung cancer trials enrolling, we know this is a critical matter for many people. Follow this link for lung cancer clinical trials that may be in your area: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=lung+cancer. Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Schabath, M. B., & Cote, M. L. (2019). Cancer progress and priorities: lung cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention, 28(10), 1563-1579. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6777859/ NIH National Cancer Institute Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (February 17, 2023) https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq NIH National Cancer Institute Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (March 2, 2023) https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq NIH National Cancer Institute What is Cancer? (October 11, 2021) https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

They say in stressful situations you should take a breath and calm down, but what if you literally can’t? Asthma is a common disease that affects around 25 million Americans. It results in several million ER visits and hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations yearly. It can also get worse over time. So what is asthma, how does it cause trouble, and what can we do about it? Take a deep breath as we dive in. To start, asthma is a medley of several related conditions that can be divided in many ways. Into allergic and non-allergic, eosinophilic and neutrophilic, adult onset, asthma with persistent airflow, asthma with obesity, and severe asthma. Several of these categories overlap and make a big mess of everything. The common threads between all types of asthma are the symptoms. Asthma is defined by its symptoms: A collection of symptoms are needed to diagnose asthma; a single symptom isn’t enough. Symptoms are also variable, getting worse at night, in the morning, or in response to a stimulus. Stimuli include irritants, allergens, exercise, infection, and weather. A pattern of symptoms in response to irritants may lead to an asthma diagnosis. Our need to breathe makes this a dangerous disease. Asthma symptoms are variable, but they all involve the airway. The airway is affected in three ways: inflammation, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and structural remodeling. Inflammation is complicated. In allergic asthma, immune cells respond to dust, pollen, and other airborne items. These are detected by defense cells in our windpipe which mistake them as dangerous. Immune cells act quickly to try and kill the “invaders”. In asthma, the big guns are brought in. Eosinophils and neutrophils are like a bazooka: highly effective at killing invaders, but can cause area-of-effect damage when used improperly. Eosinophils cause bronchial hyperresponsiveness, impaired throat function, inflammation, phlegm, and long-term allergen sensitivity. Eosinophils can also occur in non-allergic asthma. They might get involved because of genetic predisposition, polyps, viruses, and fungi. Neutrophils are similar to eosinophils in causing inflammation, but cause more severe symptoms. They generally need more irritants to activate and can be triggered by tobacco smoke, pollutants, microbes, and obesity. You can have eosinophilic or neutrophilic asthma, or both at the same time. Whatever the flavor, inflammation is the result. One of the effects of inflammation from eosinophils and neutrophils in the throat is bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Bronchial refers to the windpipe, hyper- means abnormally high, and responsiveness in this case refers to how narrow the throat gets. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness is an abnormally high constriction of the throat in response to stimuli, such as irritants. The responsiveness is temporary, leading to the characteristic variability in symptoms. Long term inflammation can cause persistent damage, called airway structural remodeling. This is when the cells of the airway grow in different ways. The walls of the airway are thickened, there is more muscle mass in the throat, the throat contracts harder, and the airway is reduced in size. This is a more permanent change in our throat, making this a long-term effect. The symptoms are very constricting, is there relief? Yes! Eosinophils respond well to anti-inflammatory medicines known as corticosteroids, like cortisone. These are used for both long-term control and for asthma attacks. Unfortunately, these don’t work on neutrophils, and can actually prolong their lifespan, exacerbating symptoms. Bronchodilators open airways and reduce swelling. Allergy-induced asthma may also be alleviated using allergy shots, tablets, or medications. Newer medicines include monoclonal antibodies that target allergens or specific cells for destruction. Medicines that directly target eosinophils or neutrophils might provide a deeper relief from asthma. Don’t hold your breath, but keep an eye out for new research opportunities! Written By Benton Lowey-Ball, BS Behavioral Neuroscience

Sources: Cockcroft, D. W., & Davis, B. E. (2006). Mechanisms of airway hyperresponsiveness. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 118(3), 551-559. https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(06)01511-9/fulltext Global Initiative for Asthma. (2000). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention updated 2022. www.ginasthma.org. Pate, C. A., Zahran, H. S., Qin, X., Johnson, C., Hummelman, E., & Malilay, J. (2021). Asthma surveillance—United States, 2006–2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(5), 1. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/ss7005a1.htm?s_cid=ss7005a1_w Pelaia, G., Vatrella, A., Busceti, M. T., Gallelli, L., Calabrese, C., Terracciano, R., & Maselli, R. (2015). Cellular mechanisms underlying eosinophilic and neutrophilic airway inflammation in asthma. Mediators of inflammation, 2015. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/mi/2015/879783/

Listen to the article here:

Eosinophilic asthma is a type of asthma that is characterized by high levels of eosinophils in the airways. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that are involved in the body’s immune response to allergens and other triggers. When eosinophils are activated, they release inflammatory chemicals that can cause damage to the airways, leading to asthma symptoms. Symptoms of eosinophilic asthma include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. These symptoms may be more severe than those of other types of asthma and may not respond as well to traditional asthma treatments like inhaled corticosteroids. Diagnosis of eosinophilic asthma involves a blood test to measure eosinophil levels and a sputum test to look for eosinophils in mucus from the lungs. Treatment may involve targeted biologic medications that specifically target eosinophils, such as mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab. These medications work by reducing the number of eosinophils in the airways, which can help to reduce asthma symptoms and improve lung function. If you or someone you know has severe asthma, clinical trials may be an option for you. Clinical trials are an important way to test new medications and treatments for asthma and other conditions. They allow researchers to gather important data on the safety and effectiveness of new treatments, and they provide patients with access to cutting-edge therapies that may not be available through traditional channels. By participating in a clinical trial, you can play an important role in advancing medical research and helping to improve the lives of people with eosinophilic asthma and other conditions. Clinical trials for this condition are currently available at ENCORE Research Group’s Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research, University Blvd. location. To learn more, you can contact us by phone, or sign up on our website. Our knowledgeable staff can guide you through the process and help you determine if a clinical trial is a good option for you.

“Pneumonia” the old man’s friend. The most frequent “sendoff” in the pre antibiotic era. In the US infectious disease remains a leading cause of death primarily due to pneumonia. Each year the bacteria Streptococcus pneumonia (pneumococcal) disease kills thousands of adults. It is spread from person to person through, coughing, sneezing and close contact. People can carry the bacteria in their throat, nose and sinuses and show no symptoms of infection and still spread the bacteria to people who do become ill. Illness can range from upper respiratory tract infections; sinus, ears and throat to much more severe disease (invasive pneumococcal disease, IPD) defined as pneumonia, blood stream infection and meningitis. There are dozens of different types of pneumococcus that vary by polysaccharides in the capsule that surrounds them.

Vaccination against pneumococcal disease started in the pediatric age group and was quickly shown to be highly effective and then introduced to the adult population with similar results. It has been proven that vaccines against pneumococcus are safe and effective and DON’T CAUSE autism. Current recommendations are that adults 65 years old should receive 2 vaccines separated by at least one year. Re-vaccination with the same vaccine is generally not recommended. PCV13 followed by PPSV23 after 1 year. The number on the vaccine tells you how many different types of pneumococcus are covered. Long term studies have shown a 75% reduction in IPD in adults after one dose of PCV13 or PPSV23 for the covered types and an overall 45% reduction against pneumococcal infections in general. Estimates for the U.S. project a vaccine related reduction of 3,000 deaths and 30,000 cases of IPD over the next 3 years.

Monitoring pneumococcal sub-types in the community allows us to produce more effective vaccines based on the sub-types identified. ENCORE Research Group is excited to participate in new pneumonia vaccine research! If you or someone you know may be interested in participating in our research, call our office to find out more!

Written By: Mitchell Rothstein, MD