GRID VIEW

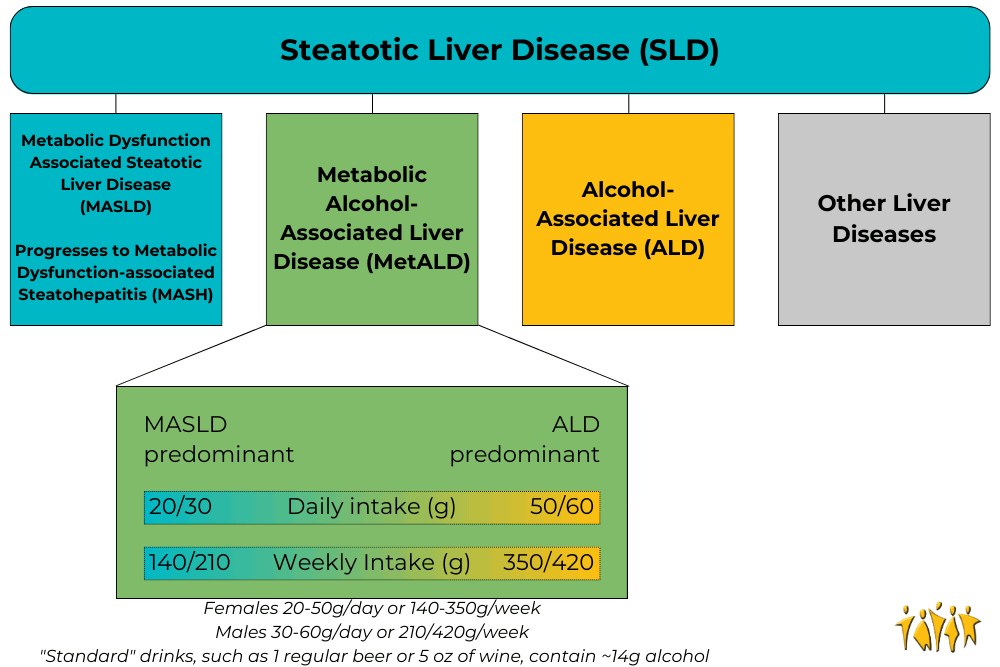

Medical terminology can be hard to understand. Much of it is in Latin, some is in Greek, several words are named after people, and terminology can change. Sometimes that change is a good thing, though. In June 2023 a collaboration of hundreds of experts in liver disease released new names for the liver diseases previously known as Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH).

Adapted from Rinella, M. E., et al., 2023

Under the broad category of Steatotic Liver Disease (SLD) we now have Metabolic dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), which can progress to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) and Metabolic Alcohol-associated Liver Disease (MetALD, which is MASLD and increased alcohol intake). This change was made for many reasons. The terms “non-alcoholic” and “fatty” may have been confusing, stigmatizing, or inaccurate. People who are not overweight may still have the disease, and those with the disease may still be consuming alcohol. Finally, naming a disease after what it isn’t (“nonalcoholic…”) is less than ideal. The new system describes the same symptoms but with more specific language. Steatosis is the accumulation of fat inside of cells and the disease is caused by changes in the metabolic system; how our cells change food into energy. A critical change has also been made with the adoption of the new term MetALD. MetALD describes people who have MASLD, but who still consume some alcohol. Alcohol affects the disease progression, but metabolic disruptions do as well. Hence, a term was developed to describe this overlap. These terms were planned and adopted by an international group of clinical researchers, scientists, educators, industry experts, and patient advocates. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL), and Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado (ALEH) made up most of the participants and have ensured widespread adoption of the new terminology Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Rinella, M. E., Lazarus, J. V., Ratziu, V., Francque, S. M., Sanyal, A. J., Kanwal, F., … & NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. (2023). A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Annals of Hepatology, 101133. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

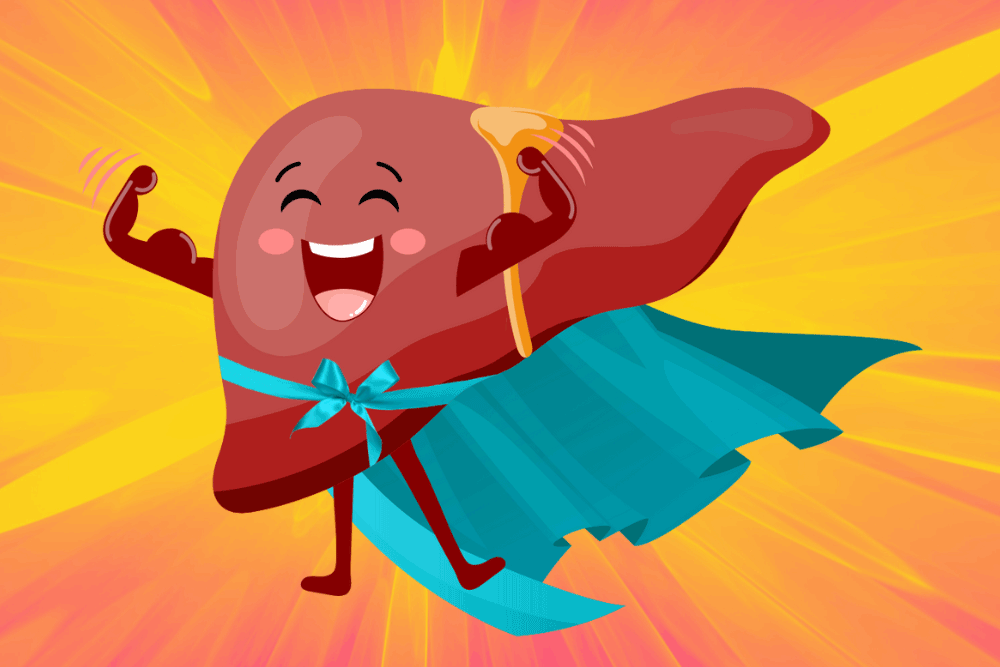

Is the liver the most amazing organ? Yes. It turns food into usable molecules. It makes proteins, bile, and hormones. It filters dangerous drugs and toxins. Without it, you would die within minutes. Also, the liver can regenerate (like a lizard’s tail!), which is basically magic. The liver is estimated to have over 500 individual functions and interacts with most body systems. In this article we’ll look at the liver, zooming in from basic facts to its cellular units. Then we’ll explore the functions of the liver. If you were to guess the largest organ in the body, would you guess the liver? I hope not, because it’s the skin. But the liver is in second place! It makes up around 2% of your body weight and usually contains about 10% of your blood. It’s located under the ribs, right below the diaphragm that inflates the lungs. It’s smooth and reddish brown when healthy (note: if you can see your liver’s color you are probably having a bad day). The liver can be divided into four parts called lobes and thousands of sub-parts called lobules. These are hexagonal columns of cells arranged so that blood can travel through carrying nutrients in and toxins and waste out. Four types of cells make up the liver: hepatocytes, epithelial cells, Kupffer cells, and stellate cells. Most of the liver is composed of hepatocytes. These are the workhorses of the liver. Hepatocytes convert fats (called lipids), sugars (called carbohydrates), and proteins (called proteins) into usable forms. They detoxify dangerous things and excrete bile and cholesterol. The barrier epithelial cells line the walls (including blood vessel walls) inside the liver and do some filtering of small particles. It is thought that these may also do some clearance of viruses. Kupffer cells are the resident immune cells. These large cells eat bacteria and debris that enter lobules. They are always touching these dangerous particles and exhibit a constant, low-level inflammation. Disruption of these cells can result in widespread, damaging liver inflammation. Finally, stellate cells store vitamin A, a critical vitamin. They are critical for promoting the liver’s amazing ability to regenerate. They form temporary scars that allow for healing. When they are damaged, however, they lose vitamin A. Damaged stellate cells can “activate” and run amok, secreting a lot of collagen that causes fibrosis and permanent scarring called cirrhosis. To understand the liver’s major functions, let’s first look at our body cells. Cells need to have a balance of chemicals to function properly. Normally cells control what goes in and out of them using special proteins. To keep unwanted things out, cells are separated from the environment around them. This separation is done by a membrane made of phospholipids. The –lipid at the end is another word for fat. Since the borders of our cells are made of fats, things that can pass through fats (called fat-soluble) can easily pass through the cell membranes. Cells can’t control this very well, so we use the liver instead. Let’s run through the liver’s major functions of storage, conversion, and creation. Storage is fairly simple. The liver stores fat-soluble vitamins and converts some of them into usable forms. It stores a quick supply of energy in the form of glycogen. Blood is stored in large quantities in the liver. This makes sense, because the liver is filtering the blood. Usually it holds a little more than 10% of the body’s blood, but the liver can expand to hold much more if needed. It can also squeeze blood out if the body is bleeding profusely. This probably isn’t great for the liver, but then again neither is bleeding out and dying. The liver converts a huge amount of material from one form into another. It acts as a gatekeeper for nearly all the blood in the body, including blood directly from the digestive tract. This includes tasty nutrients like fat and sugar, and dangerous toxins, like alcohol and methamphetamine. Blood is carried across the lobules and filtered through the hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. The liver doesn’t just remove dangerous particles, however, it metabolizes them! Metabolism is the conversion of chemicals from one form to another. One of the most important metabolic functions is detoxification. To make drugs and toxins less dangerous, the liver converts them from being fat-soluble (able to pass through cell membranes) to being water-soluble (able to be released through urine but much harder to enter cells). Carbohydrates are converted to glycogen for storage. The liver changes fats into energy for use. Proteins are broken into building blocks and waste products are removed. Remnants of dead blood cells called bilirubin are turned into bile and used for digestion. The conversion of materials into component parts helps the liver’s third broad function, creation. The liver creates, or synthesizes, many molecules that are used all around the body. It creates important hormones like angiotensin and thyroxine. It makes chemicals for the blood like prothrombin, fibrinogen, and clotting factors. It also makes the aforementioned bile, which is critical for digesting fats. The liver is the ultimate hero. Through all of these functions, the liver acts in the best interest of the body. It takes the hit from dangerous chemicals and sacrifices its own blood when we need it most. The liver is a team player of the highest degree. When it goes wrong we suffer throughout our whole body. Take care of that liver! Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Eng, F. J., & Friedman, S. L. (2000). Fibrogenesis I. New insights into hepatic stellate cell activation: the simple becomes complex. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 279(1), G7-G11. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.1.G7 Geerts, A. (2001). History, heterogeneity, developmental biology, and functions of quiescent hepatic stellate cells. In Seminars in liver disease (Vol. 21, No. 03, pp. 311-336). https://doi.org/10.1055%2Fs-2001-17550 Kalra, A., Yetiskul, E., Wehrle, C. J., & Tuma, F. (2018). Physiology, liver. https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk535438 Lautt, W. W. Hepatic Circulation: Physiology and Pathophysiology. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2009. Chapter 2, Overview. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53069/ Ozougwu, J. C. (2017). Physiology of the liver. International Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Biosciences, 4(8), 13-24. Vaja, R., & Rana, M. (2020). Drugs and the liver. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine, 21(10), 517-523. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7508170/ Yin, C., Evason, K. J., Asahina, K., & Stainier, D. Y. (2013). Hepatic stellate cells in liver development, regeneration, and cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation, 123(5), 1902-1910. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3635734/

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

The liver is an amazing and complex organ. It can regenerate from damage, helps us digest and function, filters some toxins, and in return gets thoroughly abused by us humans. Alcohol can damage the liver, but most livers are mistreated through other means, like diabetes and obesity. This is visible in the form of accumulated fat in the liver and can lead to serious problems. Nearly 1 in 4 adults in America have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). When a fatty liver becomes inflamed and damaged it is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. NASH is dangerous, and is an indication of decreased liver health. If untreated, NASH will degrade the liver, potentially leading to scarring known as fibrosis and permanent cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is cirrhiously bad. At this time, there are no approved therapies for the treatment of NASH. The current standard of care is exercise and weight loss to alleviate problems that damage the liver. Unfortunately, much like trying to lick your elbow, this is easier said than done. The consequences of an impaired liver include liver failure, cirrhosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and more. To alleviate this burden, scientists have identified several medical approaches to combating fatty liver. These approaches generally target the underlying mechanisms that lead to a fatty liver, aiming for a long-term solution. The broadest categories for investigative NASH medication are managing fat, sugar, and inflammation in the liver. One of the liver’s major jobs is to balance the body’s energy storage needs by managing fat. One method of dealing with excess fats is to dump extra fats out of the body through the digestive system. Thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β) can help us do just that. Receptors are parts of a cell that detect what’s happening outside its borders. They interact with hormones, sugars, fats, or other things. Each receptor only reacts to specific molecules. When activated, THR-β may help reduce the accumulation of fats in the liver by telling the body to move fats from the liver to the gut. Medications that activate THR-β are being investigated to see if they can also do this. Another method of helping the liver manage fat is to stop fats from being created in the first place. Unfortunately, some people create an unhealthy amount of fat. They may have a mutated gene called PNPLA3. PNPLA3 genetic disorder affects how the fat cells in the body deal with triglycerides. This mutation can increase liver fat and possibly lead to NASH. Scientists are working on ways of suppressing this gene. Other research targets being studied for limiting fat production include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα). This is a chemical receptor on liver cells that regulates how fats are processed. When activated, this receptor can lower fat creation and lead to lower blood triglycerides (the most common type of fat). Rampant activation can be dangerous, however, so very specialized Selective PPARα Modulator (SPPARMα) medications are being developed to target the system with specificity and finesse. These medications also target and activate a very interesting hormone called fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which we will cover in the next section. Fats can’t take all the spotlight, though, because one of the biggest culprits of liver damage is actually sugar. As a cookie lover, this makes me very sad. Sugars, also called glucose, are converted into fats (stored in the liver) and can damage the liver, metabolic system, heart, etc. The body detects high levels of sugar in the pancreas. High blood sugar signals the release of insulin and amylin from the pancreas to the liver. The liver then starts breaking down, converting, and storing sugars. A couple of medications look to target this system to lower the burden on the liver and help with NASH. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), mentioned above, has broad effects, including in the pancreas. It helps manage the body’s metabolism and homeostasis and makes the pancreas more sensitive to insulin. This may be particularly helpful for people with insulin resistance. Insulin resistance leads to type 2 diabetes. FGF21’s other effects appear to include increasing energy use, potentially leading to weight loss. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like Semaglutide, Trulicity, and Mounjaro, act on the same system. These directly attach to pancreatic cells, preparing them for a large insulin release when they detect high glucose levels. It is hoped that this can help the liver deal with high blood sugar without taking damage. Another potential pathway to managing blood sugar is to send it down the yellow-brick road. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors deal with blood sugar by expelling it out of the body with urine. The final target of potential NASH treatments is inflammation. NASH stands for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which literally means “non-alcoholic inflammation of the liver (due to) fat.” Inflammation is like a visit with the inlaws: good when it doesn’t last too long. Researchers hope that reducing chronic inflammation may help limit the damage of NASH and prevent a worsening of the disease. Luckily, two avenues of treatment above also target inflammation. One complication of the PNPLA3 genetic mutation is an increase in cyclophilin, a protein that can increase inflammation. By reducing excess cyclophilin through PNPLA3 management – or by targeting it directly, inflammation may be relieved. Interestingly, FGF21, which may be used to lower blood sugar, appears to lower inflammation in the pancreas. The hope is that these medical interventions may also help the liver downstream. Overall, the liver is complex, and trying to keep it from being damaged is difficult. The only real treatment available today is weight loss through diet and exercise. With luck and help from the clinical trial process, there may be new avenues available in the future. Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Fisher, F. M., & Maratos-Flier, E. (2016). Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annual review of physiology, 78, 223-241. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339 Geng, L., Lam, K. S., & Xu, A. (2020). The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: from bench to clinic. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(11), 654-667. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-020-0386-0 Prasad, A. S. V. (2019). Biochemistry and molecular biology of mechanisms of action of fibrates–an overview. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review, 26(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijbcrr/2019/v26i230094 Shen, J. H., Li, Y. L., Li, D., Wang, N. N., Jing, L., & Huang, Y. H. (2015). The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Journal of lipid research, 56(1), 167-175. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4274064/ Sinha, R. A., Bruinstroop, E., Singh, B. K., & Yen, P. M. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypercholesterolemia: roles of thyroid hormones, metabolites, and agonists. Thyroid, 29(9), 1173-1191. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6850905/ Ure, D. R., Trepanier, D. J., Mayo, P. R., & Foster, R. T. (2020). Cyclophilin inhibition as a potential treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 29(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2020.1703948 US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (April, 2021). Definition & facts of NAFLD & NASH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts Wang, P., & Heitman, J. (2005). The cyclophilins. Genome biology, 6(7), 1-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1175980/

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

Fats are tasty in food, but not particularly good in the bloodstream. They can also be toxic to the liver and cells in general. We have special cells called adipose cells that store fat in our body. These cells have defenses against dangerous fat components called free fatty acids. Free fatty acids are the high-energy parts of fats, the part that gives you energy. Fatty acids are a great way to store energy and can be turned into power for your body, but the high energy content can also be dangerous in the wrong places. The liver transforms free fatty acids into usable energy. From here, the energy is delivered to cells all over the body. The liver is part of the system that makes sure the body’s energy demands match the available energy. Unfortunately, when too many free fatty acids are delivered to the liver, they can start to build up in the liver tissue and cause damage. Fatty liver is one of the most common ailments in Western countries. One in every three to four people in the US havw a fatty liver. Excessive alcohol consumption can cause a fatty liver, but most sufferers develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Either way, people have steatosis. Steato- means fat, and -osis indicates a condition, especially an abnormal one. Steatosis of 5-10% is problematic and is the earliest indication that the liver is starting to suffer damage. Many people with fatty liver and no other abnormalities can make a full recovery, usually by stopping whatever is causing the steatosis. We know that alcohol can directly damage the liver, but how does NAFLD start? The causes are complicated, but some similarities exist. Excess fat released from fat cells, excess fat created by the liver, and excess fats from the diet all find their way into the liver. These are normally not an issue, but all are affected when the body isn’t regulating insulin properly. Insulin lets body parts know when you have food or are starving. When insulin isn’t processed correctly the body thinks it’s starving and tries to compensate – even when there is plenty of food present. In the middle of this the liver suffers. After a prolonged period of fat accumulation, a patient with NAFLD may develop non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. Steato- for fat, hepat- indicating the liver, and -itis which means inflammation. This second leg on the terrible journey develops when fat causes inflammation in the liver. The gut changes and gives the wrong signals to the liver. Cells develop insulin resistance and can’t convert sugars into energy or fats correctly. Free fatty acids cause cell problems and elicit an immune response. Stresses on the liver cause a feedback loop, where inflammation disrupts cell function. The body tries to fix the liver but can’t overcome the massive amount of dangerous fats. Cells in the liver die, and the living cells can be damaged trying to compensate. With NASH, the inflammation is long-lasting, also called chronic. The liver can regenerate from NAFLD and NASH. It can’t sustain forever, however. When the liver is permanently damaged, the tissue can scar and die. This is a permanent reduction in liver function. We call this scarring Cirrhosis. Cirros- is the Greek word for yellow-brown (the color of a dying liver), and -osis refers to a condition, especially an abnormal one. Cirrhosis has multiple stages and can be asymptomatic but cannot be recovered from without intervention. The current treatment for cirrhosis is a liver transplant. Though we’ve been talking about the dangers of fats in the bloodstream and liver, it should be noted that the body makes a lot of these fats out of carbohydrates – sugars. A healthy diet without too many sugars and with lots of exercise are the best preventative measures for these conditions. Conditions related to insulin resistance, such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome can both cause and be caused by these conditions. Also, even though we have presented these as a pathway, note that you can progress from NASH to NAFLD or become symptom-free; it’s not a one-way journey! If you have any of these conditions, talk to your primary care physician to look for solutions. Also, keep an eye out for clinical research trials that may alleviate symptoms or the underlying fat buildup.

Sources: Pierantonelli, I., & Svegliati-Baroni, G. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: basic pathogenetic mechanisms in the progression from NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation, 103(1), e1-e13. . https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002480 Sanyal, A. J. (2019). Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 16(6), 377-386.

Listen to the article here:

Fatty liver disease is incredibly prevalent in the United States. Some estimates place the number of Americans with non-alcoholic fatty liver at over 30%, that’s around 100 million people in this country! Liver diseases are deadly serious; the liver is a critical organ and without it we cannot survive. The biggest problem with all liver diseases is that they frequently progress without symptoms. Because of this, the disease may progress to a dangerous or irreversible stage before it is even detected. Clearly, early, and routine testing for people at risk is critical. We can’t see the liver from the outside, so the only way to learn about how it is doing is by looking at it. We can look through the skin using technology or under a microscope using a biopsy. A biopsy – looking at a section of the liver under the microscope – is the “gold standard” of liver diagnostic techniques. This has drawbacks, however. Patients typically need to dedicate half a day to the procedure, and there can be rare complications. A biopsy is an invasive procedure requiring a piece of the liver be taken and examined. It is a critical piece of the liver diagnosis pie but is not a routine procedure to be done without cause. Imagining techniques can be very effective in diagnosing a fatty liver. Some techniques, such as a CAT scan and ultrasound, can’t diagnose the amount of scarring on the liver but can give an indication that there is fat present. CAT scans use x-rays, but imaging is otherwise safe. An ultrasound is fast and non-invasive. It is an excellent first step that many doctors use when they suspect a fatty liver. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the next best diagnostic procedure to a liver biopsy. With an MRI, doctors can clearly see the state of the liver. They are expensive, however. This again means they are an excellent tool for those who are known to have fatty liver but may not be an option for all patients to use regularly. Ultrasonic elastography is a different technique. It is commonly called Fibroscan, after the manufacturer of the diagnostic tool. Fibroscan uses sound waves to gently shake the liver and measure how it responds. The liver will stretch slightly. In a healthy liver, the tissue stretches more, but hard scar tissue is less elastic. The fibroscan can interpret the difference and determine how much fat and scar tissue is present. The test is very similar to an ultrasound; it is painless, fast, and safe. The fibroscan does not replace other imaging techniques but is cheap and effective at determining the stage of fatty liver present. Unlike other techniques, a Fibroscan can be done routinely for anyone who is at risk of having fatty liver. Fibroscans are very popular around the world, including in Europe, Asia, South America, and Canada. It is a cheap procedure with little reimbursement for practitioners, which unfortunately prevents widespread use in the USA. Risk factors for non-alcoholic fatty liver include being overweight or obese, being prediabetic or having diabetes, and eating a high-fat diet. If you are concerned about fatty liver, talk to your primary care physician and/or contact ENCORE Research Group for a complimentary Fibroscan. Written by Benton Lowey-Ball, BS Behavioral Neuroscience

Afdhal, N. H. (2012). Fibroscan (transient elastography) for the measurement of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 8(9), 605. Koren, M. (Host). (2022, July 20). Common fibroscan technology questions [Audio podcast episode]. In Medevidence! Truth behind the data. ENCORE Research Group. https://encoredocs.com/medevidence/ Koren, M. (Host). (2022, July 13). You cannot live without your liver [Audio podcast episode]. In Medevidence! Truth behind the data. ENCORE Research Group. https://encoredocs.com/medevidence

Listen to the article here:

Healthy eating and exercise can help with not only your waistline but also cardiometabolic health. Carrying around extra fat can negatively affect your whole body; some areas of concern include the liver, heart, and joints. Although many people can maintain a healthy diet and exercise routine to keep the weight off, some folks need extra help with medication.

The liver is the largest organ inside your body and is integral in filtering harmful substances from your blood. When too much fat builds up in your liver, this is called fatty liver disease. This can progress to damaging and scarring of the liver. The scaring can ultimately lead to liver failure. Lifestyle changes, like healthy eating and exercise, are currently the only treatments for fatty liver disease, although many clinical trials are currently looking for a safe and effective therapy.

Heart disease remains the world’s leading killer. While extra fat itself does not directly cause heart attacks, it leads to other causes that can. High cholesterol, high blood pressure, and diabetes are among those that build up plaque in the arteries leading to heart attacks. ENCORE Research Group offices have many clinical trials in these areas!

Being overweight can affect your joints by raising your risk of developing osteoarthritis. The extra weight puts additional stress on your weight-bearing joints, such as your knees, which can cause additional wear and tear. Additionally, inflammation associated with weight gain might contribute to problems in other joints such as the hands.

For the folks who need more than just a healthy diet and exercise to help with medical conditions, the good news is that many new cutting-edge treatments are being studied and are available to you. Call your local ENCORE Research Group office today to get involved in our research trials.

Sources:

heathline.com

health.clevelandclinic.org

health.harvard.edu