The liver is an amazing and complex organ. It can regenerate from damage, helps us digest and function, filters some toxins, and in return gets thoroughly abused by us humans. Alcohol can damage the liver, but most livers are mistreated through other means, like diabetes and obesity. This is visible in the form of accumulated fat in the liver and can lead to serious problems. Nearly 1 in 4 adults in America have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). When a fatty liver becomes inflamed and damaged it is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. NASH is dangerous, and is an indication of decreased liver health. If untreated, NASH will degrade the liver, potentially leading to scarring known as fibrosis and permanent cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is cirrhiously bad. At this time, there are no approved therapies for the treatment of NASH. The current standard of care is exercise and weight loss to alleviate problems that damage the liver. Unfortunately, much like trying to lick your elbow, this is easier said than done. The consequences of an impaired liver include liver failure, cirrhosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and more. To alleviate this burden, scientists have identified several medical approaches to combating fatty liver. These approaches generally target the underlying mechanisms that lead to a fatty liver, aiming for a long-term solution. The broadest categories for investigative NASH medication are managing fat, sugar, and inflammation in the liver. One of the liver’s major jobs is to balance the body’s energy storage needs by managing fat. One method of dealing with excess fats is to dump extra fats out of the body through the digestive system. Thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β) can help us do just that. Receptors are parts of a cell that detect what’s happening outside its borders. They interact with hormones, sugars, fats, or other things. Each receptor only reacts to specific molecules. When activated, THR-β may help reduce the accumulation of fats in the liver by telling the body to move fats from the liver to the gut. Medications that activate THR-β are being investigated to see if they can also do this. Another method of helping the liver manage fat is to stop fats from being created in the first place. Unfortunately, some people create an unhealthy amount of fat. They may have a mutated gene called PNPLA3. PNPLA3 genetic disorder affects how the fat cells in the body deal with triglycerides. This mutation can increase liver fat and possibly lead to NASH. Scientists are working on ways of suppressing this gene. Other research targets being studied for limiting fat production include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα). This is a chemical receptor on liver cells that regulates how fats are processed. When activated, this receptor can lower fat creation and lead to lower blood triglycerides (the most common type of fat). Rampant activation can be dangerous, however, so very specialized Selective PPARα Modulator (SPPARMα) medications are being developed to target the system with specificity and finesse. These medications also target and activate a very interesting hormone called fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which we will cover in the next section. Fats can’t take all the spotlight, though, because one of the biggest culprits of liver damage is actually sugar. As a cookie lover, this makes me very sad. Sugars, also called glucose, are converted into fats (stored in the liver) and can damage the liver, metabolic system, heart, etc. The body detects high levels of sugar in the pancreas. High blood sugar signals the release of insulin and amylin from the pancreas to the liver. The liver then starts breaking down, converting, and storing sugars. A couple of medications look to target this system to lower the burden on the liver and help with NASH. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), mentioned above, has broad effects, including in the pancreas. It helps manage the body’s metabolism and homeostasis and makes the pancreas more sensitive to insulin. This may be particularly helpful for people with insulin resistance. Insulin resistance leads to type 2 diabetes. FGF21’s other effects appear to include increasing energy use, potentially leading to weight loss. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like Semaglutide, Trulicity, and Mounjaro, act on the same system. These directly attach to pancreatic cells, preparing them for a large insulin release when they detect high glucose levels. It is hoped that this can help the liver deal with high blood sugar without taking damage. Another potential pathway to managing blood sugar is to send it down the yellow-brick road. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors deal with blood sugar by expelling it out of the body with urine. The final target of potential NASH treatments is inflammation. NASH stands for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which literally means “non-alcoholic inflammation of the liver (due to) fat.” Inflammation is like a visit with the inlaws: good when it doesn’t last too long. Researchers hope that reducing chronic inflammation may help limit the damage of NASH and prevent a worsening of the disease. Luckily, two avenues of treatment above also target inflammation. One complication of the PNPLA3 genetic mutation is an increase in cyclophilin, a protein that can increase inflammation. By reducing excess cyclophilin through PNPLA3 management – or by targeting it directly, inflammation may be relieved. Interestingly, FGF21, which may be used to lower blood sugar, appears to lower inflammation in the pancreas. The hope is that these medical interventions may also help the liver downstream. Overall, the liver is complex, and trying to keep it from being damaged is difficult. The only real treatment available today is weight loss through diet and exercise. With luck and help from the clinical trial process, there may be new avenues available in the future. Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Fisher, F. M., & Maratos-Flier, E. (2016). Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annual review of physiology, 78, 223-241. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339 Geng, L., Lam, K. S., & Xu, A. (2020). The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: from bench to clinic. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(11), 654-667. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-020-0386-0 Prasad, A. S. V. (2019). Biochemistry and molecular biology of mechanisms of action of fibrates–an overview. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review, 26(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijbcrr/2019/v26i230094 Shen, J. H., Li, Y. L., Li, D., Wang, N. N., Jing, L., & Huang, Y. H. (2015). The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Journal of lipid research, 56(1), 167-175. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4274064/ Sinha, R. A., Bruinstroop, E., Singh, B. K., & Yen, P. M. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypercholesterolemia: roles of thyroid hormones, metabolites, and agonists. Thyroid, 29(9), 1173-1191. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6850905/ Ure, D. R., Trepanier, D. J., Mayo, P. R., & Foster, R. T. (2020). Cyclophilin inhibition as a potential treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 29(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2020.1703948 US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (April, 2021). Definition & facts of NAFLD & NASH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts Wang, P., & Heitman, J. (2005). The cyclophilins. Genome biology, 6(7), 1-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1175980/

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

GRID VIEW

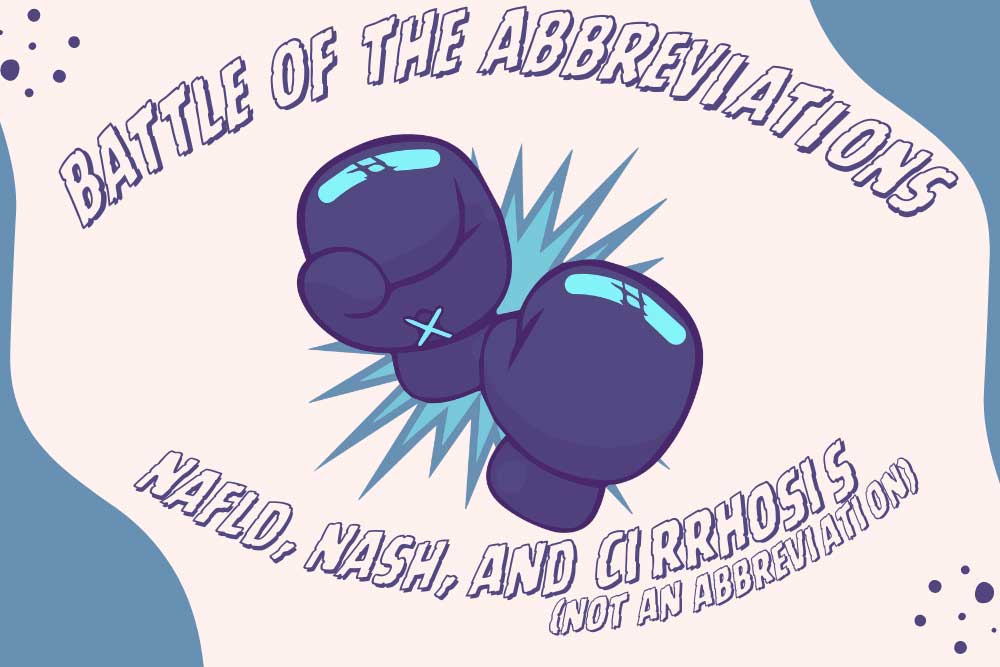

Fats are tasty in food, but not particularly good in the bloodstream. They can also be toxic to the liver and cells in general. We have special cells called adipose cells that store fat in our body. These cells have defenses against dangerous fat components called free fatty acids. Free fatty acids are the high-energy parts of fats, the part that gives you energy. Fatty acids are a great way to store energy and can be turned into power for your body, but the high energy content can also be dangerous in the wrong places. The liver transforms free fatty acids into usable energy. From here, the energy is delivered to cells all over the body. The liver is part of the system that makes sure the body’s energy demands match the available energy. Unfortunately, when too many free fatty acids are delivered to the liver, they can start to build up in the liver tissue and cause damage. Fatty liver is one of the most common ailments in Western countries. One in every three to four people in the US havw a fatty liver. Excessive alcohol consumption can cause a fatty liver, but most sufferers develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Either way, people have steatosis. Steato- means fat, and -osis indicates a condition, especially an abnormal one. Steatosis of 5-10% is problematic and is the earliest indication that the liver is starting to suffer damage. Many people with fatty liver and no other abnormalities can make a full recovery, usually by stopping whatever is causing the steatosis. We know that alcohol can directly damage the liver, but how does NAFLD start? The causes are complicated, but some similarities exist. Excess fat released from fat cells, excess fat created by the liver, and excess fats from the diet all find their way into the liver. These are normally not an issue, but all are affected when the body isn’t regulating insulin properly. Insulin lets body parts know when you have food or are starving. When insulin isn’t processed correctly the body thinks it’s starving and tries to compensate – even when there is plenty of food present. In the middle of this the liver suffers. After a prolonged period of fat accumulation, a patient with NAFLD may develop non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. Steato- for fat, hepat- indicating the liver, and -itis which means inflammation. This second leg on the terrible journey develops when fat causes inflammation in the liver. The gut changes and gives the wrong signals to the liver. Cells develop insulin resistance and can’t convert sugars into energy or fats correctly. Free fatty acids cause cell problems and elicit an immune response. Stresses on the liver cause a feedback loop, where inflammation disrupts cell function. The body tries to fix the liver but can’t overcome the massive amount of dangerous fats. Cells in the liver die, and the living cells can be damaged trying to compensate. With NASH, the inflammation is long-lasting, also called chronic. The liver can regenerate from NAFLD and NASH. It can’t sustain forever, however. When the liver is permanently damaged, the tissue can scar and die. This is a permanent reduction in liver function. We call this scarring Cirrhosis. Cirros- is the Greek word for yellow-brown (the color of a dying liver), and -osis refers to a condition, especially an abnormal one. Cirrhosis has multiple stages and can be asymptomatic but cannot be recovered from without intervention. The current treatment for cirrhosis is a liver transplant. Though we’ve been talking about the dangers of fats in the bloodstream and liver, it should be noted that the body makes a lot of these fats out of carbohydrates – sugars. A healthy diet without too many sugars and with lots of exercise are the best preventative measures for these conditions. Conditions related to insulin resistance, such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome can both cause and be caused by these conditions. Also, even though we have presented these as a pathway, note that you can progress from NASH to NAFLD or become symptom-free; it’s not a one-way journey! If you have any of these conditions, talk to your primary care physician to look for solutions. Also, keep an eye out for clinical research trials that may alleviate symptoms or the underlying fat buildup.

Sources: Pierantonelli, I., & Svegliati-Baroni, G. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: basic pathogenetic mechanisms in the progression from NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation, 103(1), e1-e13. . https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002480 Sanyal, A. J. (2019). Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 16(6), 377-386.

Listen to the article here:

The liver is an amazing and necessary organ. It can regenerate from a minor injury, break down dangerous chemicals and drugs, and help maintain the proper balance of nutrients, fats, and sugars in the body. It has hundreds of other important roles as well. With all this responsibility, we are in trouble when the liver stops working. One way the liver stops working is through non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Steato- means fat, hepato- indicates the liver, and -itis means inflammation. Steatohepatitis is inflammation of the liver caused by fat accumulation. This is a progressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – the most common liver disorder in western countries. Progressive means that this disease gets more severe over time. NASH is a large problem in America, affecting 3-12% of adults. Furthermore, NASH can lead to cirrhosis, where the liver is permanently damaged, and lead to possible liver transplantation. Over a million adults in America have NASH-related cirrhosis. How do we get NASH? As the name indicates, this is not caused by alcohol. There are many pathways to developing NASH, but the underlying cause may be excess carbs and fatty acids. This can be due to diet or behavior, underlying genetics, or associated syndromes. Some of the syndromes associated with NASH are: The underlying mechanism of NASH can be very complex. A leading precursor to NASH is insulin resistance, where cells fail to respond to insulin. Conditions that cause or are caused by insulin resistance, such as type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome, may increase your chances of developing NASH. They also may develop or worsen as NASH symptoms get worse. Insulin resistance causes different types of fats to accumulate in the liver. This makes it very difficult for the liver to process the fats and they ultimately build up in liver cells. These fats, especially ones called nonesterified fatty acids (NFEAs), are very dangerous. They cause damage to liver cells and can also activate cytokines that start the inflammation process. Eventually, we get NASH, an inflammation cascade in the liver caused by fats. Cytokines start inflammation in the liver. Cell death attracts the immune system, which enters and causes inflammation while trying to help. Liver cells die and are less able to process fats, which leads to a compounding effect. Eventually, we may transition to cirrhosis, where permanent liver scarring and damage occur. There are few treatments on the market for NASH. As usual, the primary therapy for NASH is a good diet and regular exercise. Medicinal remedies are all in the experimental phases. Potential targets include increasing insulin sensitivity, decreasing fat creation, decreasing circulating fats, breaking fats down, and anti-inflammation treatments. One way to decrease circulating fats is by expelling them through the digestive system. In the liver, moving fats to the gut is regulated by thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones activate receptors, which exist all over the body and cause many different effects. Thyroid hormone receptor Beta (THR-β) exists almost exclusively in the liver. Scientists are working to create medicines that activate THR-β and help clear fats from the liver in NASH patients. If you are interested in participating in a research study, contact your local ENCORE Research Group site today!

Sources: Noureddin, M., & Sanyal, A. J. (2018). Pathogenesis of NASH: the impact of multiple pathways. Current Hepatology Reports, 17, 350-360. Parthasarathy, G., Revelo, X., & Malhi, H. (2020). Pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an overview. Hepatology communications, 4(4), 478-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1479 Pierantonelli, I., & Svegliati-Baroni, G. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: basic pathogenetic mechanisms in the progression from NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation, 103(1), e1-e13. . https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002480 Pramfalk, C., Pedrelli, M., & Parini, P. (2011). Role of thyroid receptor β in lipid metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 1812(8), 929-937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.019

Listen to the article here:

The liver is critical to maintain body function. Unfortunately, millions of Americans suffer from liver disease. When the liver suffers prolonged damage, scarring can form. This scarring, called cirrhosis, is debilitating and reduces liver function. Cirrhosis is sometimes called end stage liver disease, and is irreversible. On its own, cirrhosis can be painful and cause suffering, but is frequently made worse through complications. One of these is encephalopathy. Encephalopathy is a broad term used to describe several diseases and disorders. The unifying concept is that these diseases change the brain’s structure or function. When the cause of this change is through cirrhosis, the condition is called hepatic encephalopathy. This is the condition caused by cirrhosis of the liver, and can be horrible. It comes with a high mortality rate, over 25%, and affects over 30% of people with cirrhosis. The full mechanism of how hepatic encephalopathy works isn’t fully known. The most likely candidate for hepatic encephalopathy is a buildup of ammonia in the bloodstream. Ammonia is a common waste product for many cells. A damaged liver has trouble filtering ammonia from the blood. The ammonia accumulates in the blood where it can travel to the brain and cause confusion and disorientation at first. Additionally, liver damage can result in reduced muscle mass and immunosuppression. Muscles can remove excess ammonia from the blood, but may become damaged without a functional liver and be unable to help. A reduced immune system can lead to a buildup of harmful bacteria that produce excess ammonia. These combine to create excess toxic levels of ammonia in the bloodstream that make their way to the brain. The brain is normally protected from toxins in the blood through the blood brain barrier. Astrocytes are special cells in the brain that surround blood vessels and help filter the blood, letting only specific nutrients and particles through. Excess ammonia in the blood appears to damage astrocytes, with wide ranging effects on the brain. When the blood-brain barrier is reduced, toxins can enter the brain. This can lead to damage in neurotransmission, meaning the brain cannot function effectively. There is also an increased chance of infection in the brain and alterations to brain metabolism. This is a devastating compilation which can drastically reduce quality of life. In the early stages of hepatic encephalopathy, people may experience a general slowing of the brain. This is noticeable in attention, some motor response, and other vague areas. As the encephalopathy progresses, people experience more severe symptoms. Changes in personality have been reported, such as irritability and impulsivity. They may angrily buy m&ms in the checkout line. It also slows the brain and reduces its ability to function. People may become disoriented, experience distortions of time and space, become excessively sleepy, and descend into a coma. Clearly this condition needs medical attention! Luckily, hepatic encephalopathy can be reversible in many patients! The most important short-term treatment is to get rid of excess blood ammonia. The current standard of care is lactulose, a chemical that binds to ammonia and expels it rectally. This helps in the short term, and can also be recommended to help reduce recurrence. Though effective, lactulose is a laxative and can cause bloating, cramping, and other undesirable side effects. Because of this, many patients don’t like using this drug long term. Since the immune system is suppressed with cirrhosis, antibiotics may help as well. In fact, antibiotics may be helpful in preventing hepatic encephalopathy in the first place by eliminating harmful, ammonia producing bacteria before they can produce too much ammonia. Used with or without probiotics and drugs that help restore normal brain chemistry, we may be able to lower the burden of hepatic encephalopathy for those who suffer. Written by Benton Lowey-Ball, BS Behavioral Neuroscience

Sources: Bustamante, J., Rimola, A., Ventura, P. J., Navasa, M., Cirera, I., Reggiardo, V., & Rodés, J. (1999). Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology, 30(5), 890-895. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80144-5 Ferenci, P. (2017). Hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology report, 5(2), 138-147. https://doi.org/10.1093/gastro/gox013

Listen to the article here: