GRID VIEW

Alzheimer’s disease is probably my biggest fear. Unfortunately, this means the anxiety surrounding it can also be debilitating. If I forget a coworker’s name, is that a sign? What if I “forget” that pizza is not on the whole 30 diet? Jokes aside, worrying about Alzheimer’s can interfere with daily life. So, how can you differentiate between the normal lapses we all get, changes due to aging, and the serious brain alterations that occur during Alzheimer’s dementia? On the MedEvidence!™ Podcast Neurologist Stephen Toenjes, MD, describes the key factor of Alzheimer’s, “there are normal changes that are associated with aging. But we do not lose our memory as we age. If there’s memory loss, there is something wrong. There is damage [1].” He continues by having us imagine “somebody put the milk in the cabinet. I just ask, ‘Where does the milk go?’ And the patient will say ‘In the refrigerator’. And that illustrates that the person knows that the milk goes in the refrigerator. They didn’t forget that it goes in the refrigerator, they just weren’t paying attention to what they were doing. [1]” A patient with Alzheimer’s would not remember where the milk goes. This differentiation between brain changes due to normal aging and those due to Alzheimer’s can pose real challenges for doctors; diagnosing Alzheimer’s can be a long and complex process [2]. Many of the steps to diagnose Alzheimer’s are investigations into other things that may be causing mental changes. Unfortunately, there are currently no cures for Alzheimer’s dementia, though clinical trials are actively attempting to fill this void [2]. An early diagnosis may be particularly important for those seeking a clinical trial for Alzheimer’s because the disease gets worse over time. We may not be able to reverse the effects of Alzheimer’s dementia, but the earlier a patient receives treatments being developed, the more effective they can be at preventing decline [2]. Creative Director Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: [1] Koren, MJ. Toenjes, S. & McKormick, M. (13 April, 2022). Is it Alzheimer’s or something else? In MedEvidence! Truth Behind the Data [Podcast]. [2] National Institute on Aging. (8 December, 2022) How is Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-alzheimers-disease-diagnosed [3] Jack Jr, C. R., Andrews, J. S., Beach, T. G., Buracchio, T., Dunn, B., Graf, A., … & Carrillo, M. C. (2024). Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 20(8), 5143-5169. https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/alz.13859

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

https://medevidence.com/dementia-vs-alzheimers

Alzheimer’s Dementia, often shortened to AD, is abjectly terrible. People with the disease lose memories, language, and the ability to function by themselves. It was first described over a hundred years ago by Dr. Alzheimer, and there has been startlingly little progress in treating the disease since. Alzheimer’s disease is a dementia characterized by two kinds of brain deposits: amyloid plaques and tau tangles. It’s the most common type of dementia. Dr. Alzheimer also noticed the distinct presence of extra cholesterol in the brain, which we will return to. We have few medications that are approved to help with Alzheimer’s. Even these don’t cure the disease but instead slow its progress. This indicates a fundamental lack of a good model for how the disease starts or progresses. The first big hypothesis for Alzheimer’s was the cholinergic hypothesis; that there is a paucity of a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine causing the damage. Unfortunately, drugs that increase acetylcholine don’t stop the disease progression. The second big hypothesis, the one that is currently in vogue, is the amyloid cascade hypothesis. According to this theory an amyloid precursor known as amyloid beta (Aβ) is the cause of Alzheimer’s. This makes a lot of sense, as Aβ is the main component of amyloid plaques and people with a genetic predisposition to make extra Aβ tend to get Alzheimer’s (called familial Alzheimer’s). There are a few inconsistencies in this hypothesis: the distribution of Aβ doesn’t match how bad the disease is, and risk factors that increase Aβ don’t match those of Alzheimer’s. To make matters worse, in spite of decades of research, over 99% of clinical research studies targeting Aβ have failed to bring a medication to market.1 Enter the Lipid Invasion Model. This is a new hypothesis developed in 2021 to explain the root cause of Alzheimer’s dementia. The basic idea is that the barrier between the brain and the rest of the body degrades, which allows cholesterols and free fatty acids to “invade” the brain and cause damage. The less basic idea is the rest of this article. To begin, let’s discuss the barrier between the brain and the body, aptly called the Blood Brain Barrier. The barrier is made up of the blood vessels of the brain. These are special blood vessels with unique properties. The cells that make up the walls of the blood vessels, called epithelial cells, are joined together with tight junctions that keep small charged particles from getting past. These epithelial cells are dotted with special transporters that only let in certain nutrients. Other brain cells called pericytes and astrocytes surround the epithelial cells (on the brain side) and keep out stragglers. This allows the brain to maintain the environmental conditions that it needs to function. Instead of letting a free flow of blood to cells, the blood brain barrier only lets in specific amounts of specific nutrients. One of the key items that is restricted by the blood brain barrier is lipids. “Lipids” is another name for fats. In the body they perform several vital functions, and in the brain they are critical. Even though the brain is only 2% of the body’s weight, it contains nearly a ¼ of the body’s cholesterol. It uses this for cell repair, creating synapses (learning), releasing communication particles, and for coating neurons to increase the speed of thought. The two lipids relevant to this discussion are cholesterol and free fatty acids. These are energy-dense particles that don’t dissolve in watery liquids like blood. Instead, they need to hitch a ride to be transported through the bloodstream. In the brain, cholesterols and free fatty acids must be transported in small, dense, protein-rich particles called lipoproteins. In the body, lipoproteins come in many different sizes (including low-density lipoproteins, known as LDL). In addition, free fatty acids can be transported in a different protein called albumin. Part of the blood brain barrier’s job is to keep these two systems of transporting lipids separate. The Lipid Invasion Model postulates that this separation system fails. When this happens the brain can’t handle the extra lipids. Free fatty acids in particular have a detrimental effect. They cause oxidative stress that can result in cell damage and change the energy regulation of neurons, causing problems, and activating immune receptors causing an inflammatory response. Inflammation can result in astrocyte cells producing extra cholesterol, making the problem worse. On top of this, excess lipids in the brain are thought to limit the ability of neurons to grow and cause the amnesia typical of Alzheimer’s. Finally, excessive lipids may cause the brain to create amyloid beta, the precursor to the stereotypical amyloid plaques. So what goes wrong with the blood brain barrier? Scientists think the barrier degrades over time. Those tight junctions loosen, the transporters let in too many items, or items of the wrong type, and different proteins on the surface of epithelial cells disrupt the barrier. Additionally, microbleeds in the brain let unrestricted blood flow through and interact without the epithelial cells’ consent. The barrier lets the wrong type of materials cross, including lipids. In Alzheimer’s patients, we see free fatty acids and non-brain-native lipoproteins (including the risky APOE4) spread through the brain. The risk factors for blood brain barrier damage are eerily similar to those of Alzheimer’s dementia: So what can we do with this new hypothesis? The most important step is to research it! I need to reiterate that this is only a hypothesis. It’s still only a few years old, and there is no experimental data verifying the veracity of this very vivacious version of Alzheimer’s. There is some early evidence the lipid invasion model may have merit; people on lipid-lowering statin medication have significantly lower rates of Alzheimer’s. If experimentation verifies the hypothesis, we may see new methods of targeting Alzheimer’s, hopefully with a much higher success rate! Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Chaves, J. C., Dando, S. J., White, A. R., & Oikari, L. E. (2023). Blood-brain barrier transporters: An overview of function, dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and strategies for treatment. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 166967. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/244794/1/151230849.pdf 1Cummings, J. L., Morstorf, T., & Zhong, K. (2014). Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer’s research & therapy, 6(4), 1-7. https://alzres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/alzrt269?_ga=2.232085279.1814812906.1525132800-565150820.1525132800 Hu, Z. L., Yuan, Y. Q., Tong, Z., Liao, M. Q., Yuan, S. L., Jian, Y., … & Liu, W. F. (2023). Reexamining the Causes and Effects of Cholesterol Deposition in the Brains of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecular Neurobiology, 60(12), 6852-6868. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12035-023-03529-y Jick, H. Z. G. L., Zornberg, G. L., Jick, S. S., Seshadri, S., & Drachman, D. A. (2000). Statins and the risk of dementia. The Lancet, 356(9242), 1627-1631. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(00)03155-X/abstract Rudge, J. D. A. (2022). A new hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: The lipid invasion model. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, 6(1), 129-161. https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease-reports/adr210299 Rudge, J. D. A. (2023). The Lipid Invasion Model: Growing Evidence for This New Explanation of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, (Preprint), 1-14.https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad221175#ref007 Wang, H., Kulas, J. A., Higginbotham, H., Kovacs, M. A., Ferris, H. A., & Hansen, S. B. (2022). Regulation of neuroinflammation by astrocyte-derived cholesterol. bioRxiv, 2022-12. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.520161 Xiong, H., Callaghan, D., Jones, A., Walker, D. G., Lue, L. F., Beach, T. G., … & Zhang, W. (2008). Cholesterol retention in Alzheimer’s brain is responsible for high β-and γ-secretase activities and Aβ production. Neurobiology of disease, 29(3), 422-437. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2720683/

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Listen to the article here:

I have two cats. They seem pretty smart, there’s definitely something going on in their minds. Unfortunately, I can’t see inside their thoughts, so it is hard for me to know just how capable they really are. Weirdly, this isn’t just a problem with cats, but people too. Many of us have the ability to talk, type, sign, or draw, but even with our most precise communication methods, it is impossible to find out what’s actually going on up there. The modern form of this problem was clearly explained in the 1960’s by the founders of cognitive psychology, the study of how people think. Cognition is a challenging field to study because even with imaging technologies that can look inside the brain, like MRIs and CAT scans, we can’t ever really know how a person is thinking. We can study the inputs and outputs, we can study how neurons fire, and we can look at the overall state of the brain, but the individual subjective experience escapes us. An example of subjective experience is color. Our experiences of color can be altered by external factors like tinted sunglasses, cataracts, and eye deformities, but we can also change it just by staring at a bright color for a long time, being out in the sun and coming inside, or even through the language we use to describe colors! Cognition is an interesting area of study but has real-world consequences. One of the challenges with the complexity of cognition and our subjective experience is gauging the presence and severity of mental decline. Unlike diabetes, where we can measure the amount of glucose in the blood, with mental decline and dementia, we have to rely on tests of cognition to measure how well or poorly someone performs cognitive tasks. The benchmark Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) is the most widely used tool. MMSE is a relatively short (5-15 minute), untimed set of 20 questions that measure 11 domains of cognition: The MMSE can be repeated to track changes over time. The test alone is not a diagnostic tool; a low score does not confirm mental decline and further testing would be needed. Further, age and education level can also lead to lower scores. A high score, however, is unlikely in patients with dementia. This makes the MMSE a great tool for screening patients and quickly assessing patients who fear they may be slipping cognitively. Now, they need to make one for cats based on meows and mice. ENCORE Research Group provides complimentary Mini Mental State Examinations (MMSE) at designated research locations for individuals over the age of 60 who are worried about experiencing memory loss beyond what is considered age-appropriate. Those locations include: Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References: Yoo, S. G. K., Chung, G. S., Bahendeka, S. K., Sibai, A. M., Damasceno, A., Farzadfar, F., … & Flood, D. (2023). Aspirin for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in 51 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. JAMA, 330(8), 715-724. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.12905 Esenwa, C., & Gutierrez, J. (2015). Secondary stroke prevention: challenges and solutions. Vascular health and risk management, 437-450. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S63791 American Heart Association News. (April 4, 2019). Proactive steps can reduce chances of second heart attack. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/04/04/proactive-steps-can-reduce-chances-of-second-heart-attack American Heart Association. (2022). 5 ways to lower your risk of a second heart attack. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/health-topics/heart-attack/5-ways-to-lower-your-risk-of-second-heart-attack-infographic.pdf Karlin, R., Wojcik, S., Kang, S. (2024). Preventing a second heart attack. University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=56&contentid=2446 de Jong, M., van der Worp, H. B., van der Graaf, Y., Visseren, F. L., & Westerink, J. (2017). Pioglitazone and the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. A meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Cardiovascular diabetology, 16(1), 1-11 .https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5644073/

Scroll down to listen to this article.

Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research (904) 730-0166

Fleming Island Center for Clinical Research (904) 621-0390Listen to the article here:

Alzheimer’s Disease is a devastating brain disorder that gets worse over time. Early onset Alzheimer’s occurs before age 65. Most early Alzheimer patients develop symptoms in their 40s and 50s with some particularly aggressive forms starting as early as the late 20s. Any form of Alzheimer’s is a tragedy, but early onset Alzheimer’s can be particularly cruel. We do not know exactly what causes Alzheimer’s Disease. We do know that there are genetic and environmental causes that seem to mix with a high amount of randomness. We also know that some diseases exist alongside Alzheimer’s and may be risk factors. These include diabetes, hypertension, cholesterol issues, and metabolic syndrome. Alzheimer’s produces a number of terrible symptoms: Together, these symptoms combine into cognitive decline, loss of independence, and death. Early onset Alzheimer’s can have these symptoms, but is also more aggressive with shorter lifespan and larger changes in the brain. Interestingly, up to a quarter of patients with early Alzheimer’s may develop cognitive decline without memory loss. This can present as trouble with: We are still uncertain how genetic and environmental conditions translate into Alzheimer’s but the leading theory involves an accumulation of protein in the brain called amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Amyloid plaques are a buildup of a protein between neurons. It is thought that this buildup somehow causes the accumulation of tau inside of neurons. Tau is another protein that folds incorrectly and tangles up inside of neurons, leading to their eventual death. It has been very difficult to study the root causes of Alzheimer’s. This is in large part because of the inconsistency of who gets it. This also means that creating medications for Alzheimer’s has been difficult. One of the most promising avenues for study has been targeting amyloid plaques for disposal by the immune system. With luck, research can pin down a treatment to help slow or even stop the march of early Alzheimer’s. If you would like to be screened for Alzheimer’s, a free Memory Assessment is available at the Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research at 4085 University Boulevard, South, Suite 1, Jacksonville, FL 32216. Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

Sources: Ayodele, T., Rogaeva, E., Kurup, J. T., Beecham, G., & Reitz, C. (2021). Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: what is missing in research?. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 21, 1-10. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11910-020-01090-y Mintun, M. A., Lo, A. C., Duggan Evans, C., Wessels, A. M., Ardayfio, P. A., Andersen, S. W., … & Skovronsky, D. M. (2021). Donanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(18), 1691-1704. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2100708 Reitz, C., Brayne, C., & Mayeux, R. (2011). Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology, 7(3), 137-152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3339565/

Listen to the article here:

Methods used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease are changing. In the past, the only definitive way to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease was after death, by an autopsy, which is not exactly helpful for treatment. The autopsy would reveal both amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain; these are hallmarks that characterize Alzheimer’s disease. Thankfully, science has drastically improved over the years. We currently have spinal fluid tests that look for these two key biomarkers and imaging tests that show changes in the brain. A recent example of other evolving diagnosis methods is COVID-19. Early in the pandemic, when there were no COVID-19 tests, the only way to know if someone might have the virus was to check for a fever. Nowadays, we look for biomarkers – such as with a rapid antigen test – which can detect antigens to the virus even in asymptomatic people. We now understand that a person can be suffering from the progressive nature of Alzheimer’s even if they do not yet show signs of cognitive impairment. Without biomarker testing, most patients’ first symptoms are memory loss, including long and short-term. Alzheimer’s is usually associated with increased age because the biological underpinnings of the disease accumulate over time. Diagnosis can be made by using something called the ATN framework. This framework describes the two major proteins involved, amyloid plaques and tau tangles, and the associated neurodegeneration – changes in the brain structure.

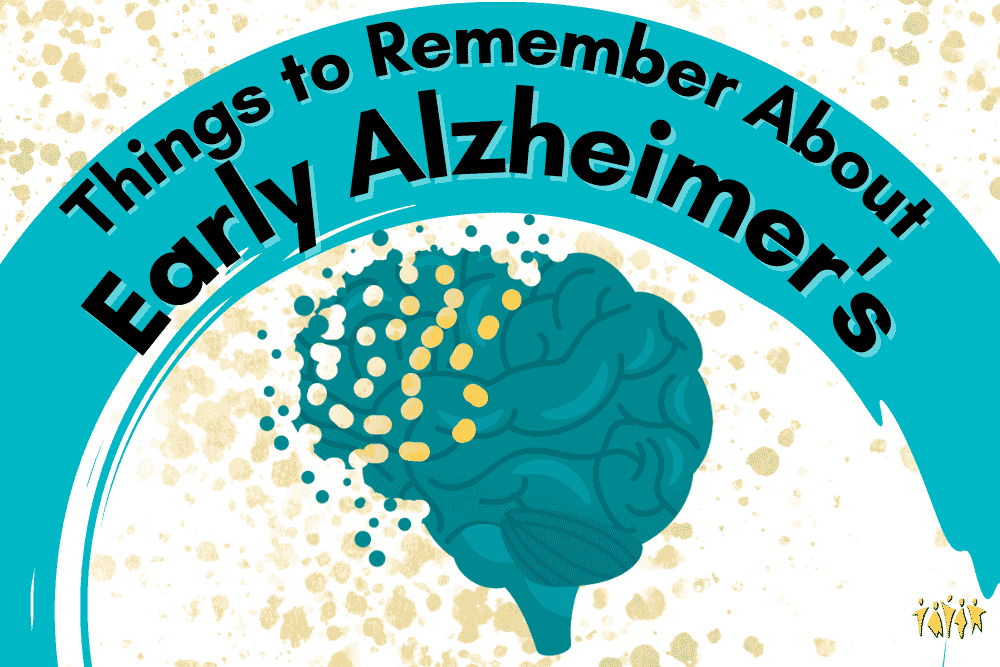

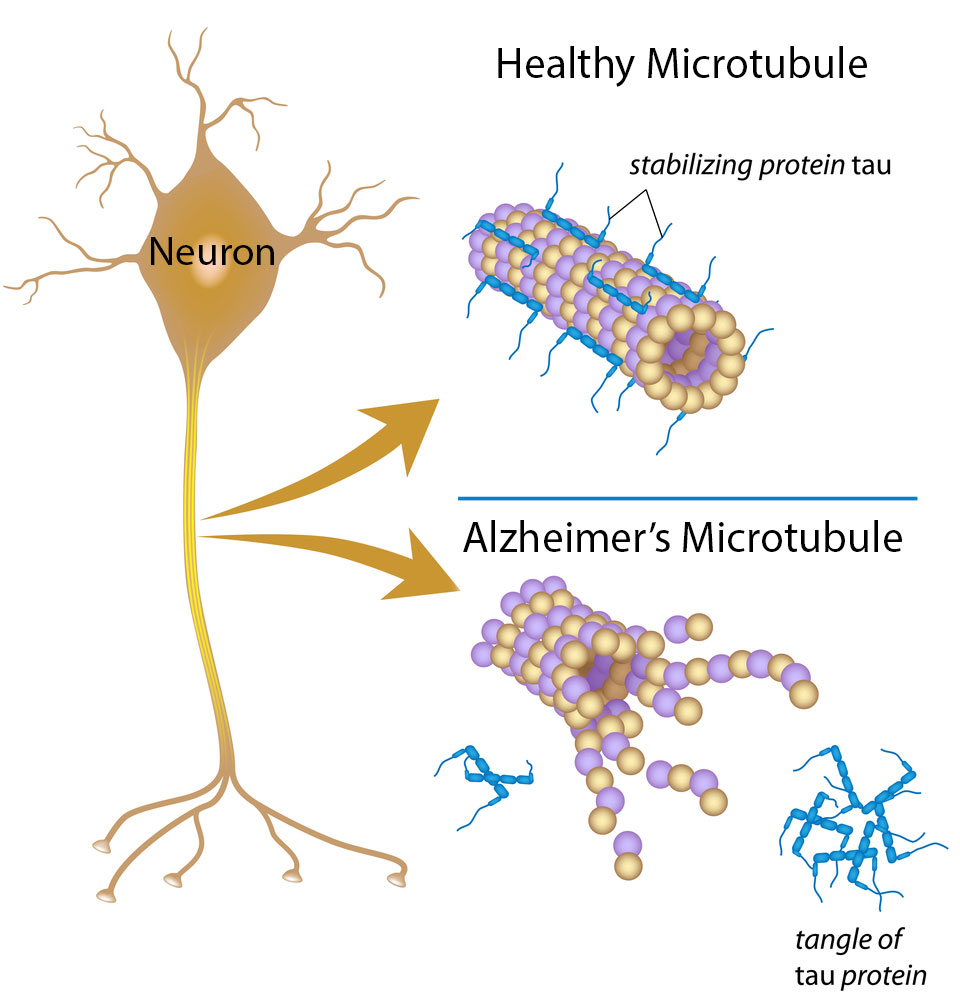

Let’s discuss the AT part of ATN: the two protein accumulations called amyloid plaques and tau tangles. It is no coincidence that these are also the biomarkers sought by scientists and doctors when diagnosing Alzheimer’s. Amyloid plaques are bundles of protein that build up outside of cells in the brain. They disrupt how cells connect and communicate with each other. Tau tangles are proteins found inside the neurons. In a healthy neuron, tau proteins help stabilize the microtubule that transfers nutrients. In Alzheimer’s patients, the tau proteins become corrupted and tangled, blocking the neuron’s transport system. This leads to cell death. As more cells die and neural network connections break down, areas in the brain begin to shrink. In the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, there is widespread loss of brain volume.

The N of ATN is neurodegeneration which is the deterioration of neurons causing specific structural changes to the brain. A structural MRI and a radioactive PET scan are two classic methods of determining neurodegeneration. These are effective as staging tools, discovering how far along the disease has progressed. They are effective but can be expensive and time-consuming. The good news is that researchers are currently working on blood tests that will hopefully be able to detect tau biomarkers quickly and easily. A blood test should be easy, cheap, and relatively simple. With luck, these early biomarker findings will also help drive the effectiveness of clinical therapies, paving the way for better Alzheimer’s treatments in the years to come. By Benton Lowey-Ball, BS Behavioral Neuroscience

Sources: Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H., Jessell, T. M., Siegelbaum, S., Hudspeth, A. J., & Mack, S. (Eds.). (2000). Principles of neural science (Vol. 4, pp. 1149-1159). New York: McGraw-hill. Largent, E. A., Wexler, A., & Karlawish, J. (2021). The Future Is P-Tau—Anticipating Direct-to-Consumer Alzheimer Disease Blood Tests. JAMA neurology, 78(4), 379-380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4835 Ossenkoppele, R., Reimand, J., Smith, R., Leuzy, A., Strandberg, O., Palmqvist, S., … & Hansson, O. (2021). Tau PET correlates with different Alzheimer’s disease‐related features compared to CSF and plasma p‐tau biomarkers. EMBO molecular medicine, 13(8), e14398. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202114398 Peterson, R. C. [UCI MIND] (2019, April 3). Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers – Ronald C. Petersen, MD, PhD [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtS5xynes2M What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease? (2017, May 16) National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-happens-brain-alzheimers-disease

Listen to the article here:

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a disorder that is often diagnosed in childhood. When most people think of ADHD, they envision young children with an overabundance of hyperactivity and impulsiveness. However, there are three kinds of ADHD: hyperactive, inattentive, and combined presentation (inattentive and hyperactive). Researchers feel that inattentive ADHD is underdiagnosed because the symptoms present quite differently and are less noticeable. It is a chronic condition that causes attention difficulties, hyperactivity, mood swings, and impulsiveness.

In more recent years, it has come to light that ADHD might be associated with some memory loss. Other common reasons for memory loss include brain injuries, illnesses like Alzheimer’s or depression, effects of drugs and alcohol, and nutritional deficiencies. Other examples that can cause memory loss are age, stress, or lack of sleep.

Many people with ADHD go undiagnosed, especially if they have inattentive ADHD. Adults with ADHD do report memory loss, especially long-term memory. More recent studies have focused on why adults with ADHD have memory loss.

An article under the National Library of Medicine states that “it is well documented that adults with ADHD perform poorly on long-term memory tests. ”Their study concluded that adult ADHD reflects “a learning deficit induced at the stage of encoding.”

Researchers aren’t clear about ADHD and memory loss or whether having ADHD as an adult puts you at higher risk for developing dementia. Another study done in 2017 discussed the overlapping symptoms of ADHD and a type of dementia called mild cognitive impairment.

Continued research is essential to increase understanding of ADHD and the link between memory loss. ENCORE Research Group sites do not currently have any research studies for ADHD, but you can find some by searching clinicaltrials.gov. If you are experiencing memory loss, it’s vital to speak with your doctor about your symptoms. If you are over 50 and have memory loss, Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research offers a free memory screening assessment. You can contact us at (904)-730-0166.

Sources:

Skodzik T, Holling H, Pedersen A. Long-Term Memory Performance in Adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2017 Feb;21(4):267-283. doi: 10.1177/1087054713510561. Epub 2016 Jul 28. PMID: 24232170.

Callahan, B. L., Bierstone, D., Stuss, D. T., & Black, S. E. (2017). Adult ADHD: Risk Factor for Dementia or Phenotypic Mimic?. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 9, 260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00260

Listen to the article here:

Could our guts affect how smart we are? A new study of over 14,000 women provides evidence. The study followed middle aged, 50-60 year old women over seven years from 2014 to 2018. It found that the longer a person used antibiotics, the greater the mental decline. At the high end, two months of antibiotic use was correlated with a mental decline equal to aging an extra 3-4 years.

This study does not imply causation. All participants self-reported their data, meaning they answered questionnaires. This does not allow scientists to see a direct cause-effect relationship. Other confounding effects may have been in play. One is that participants who used more antibiotics were more likely to have been sick. The scientists in charge of this study attempted to account for these differences. Study scientists adjusted for:

- Age and socioeconomic factors (education level, spousal education level)

- Lifestyle (smoking, alcohol use)

- General health (weight, physical activity, eating habits, multivitamin use)

- Mental health (depression, antidepressant use)

- Cardiovascular health (heart medication, blood pressure, cholesterol, history of heart attack)

- Other big health issues (stroke, diabetes, emphysema)

After this they still found that antibiotic use was the leading indicator of mental decline.

The link between the gut and the brain is an area of intense and active investigation. Information can travel back and forth between the gut and the brain along a special route called the gut-brain-axis. This takes advantage of a large nerve, the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve directly links the digestive tract and the brain. Animal studies show that altering the gut bacteria can alter a host of mental processes. In developing animals, reducing gut bacteria alters how their brains develop. Animal stress hormone levels also vary in response to changes in gut bacteria levels. Several of these changes reverse or decline when normal bacterial levels are restored. More experimental information could help solidify the link between the gut and the brain.

Mehta, R. S., Lochhead, P., Wang, Y., Ma, W., Nguyen, L. H., Kochar, B., … & Chan, A. T. (2022). Association of midlife antibiotic use with subsequent cognitive function in women. Plos one, 17(3), e0264649.

Sources:

Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of gastroenterology: quarterly publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, 28(2), 203.

Heijtz, R. D., Wang, S., Anuar, F., Qian, Y., Björkholm, B., Samuelsson, A., … & Pettersson, S. (2011). Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 3047-3052.

Alzheimer’s is a devastating disease that affects 5.5 million people of all ages in the United States. Along with the diagnosis and reality of living with this disease, the families of these patients are now left with the question, “how will we take care of our loved one?” For many families, the option is having a designated person take care of the patient on their own. A caregiver is someone that assists with the daily needs of another person. There can be a “formal” caregiver, considered a paid person along with training, and an “informal” caregiver is a family or friend who provides care without pay. It can be a challenge for informal caregivers, especially with no training. Around 65.7 million people in the United States are informal caregivers. With that large of a statistic affecting a specific population, there are always great tips that can be provided.

Asking For Help

Taking care of someone with Alzheimer’s can be challenging. If it becomes too difficult for a caregiver, sometimes they feel guilty in asking for help. If taking care of someone becomes too emotionally and physically draining, there’s no shame in asking for help or even hiring someone to come in and help. The most important thing is making sure that your loved ones can get the best care they can get.

Staying Connected

Studies show that caregivers who stay in touch with their families and friends have better emotional health than those who feel isolated. Reaching out to express your feelings about being a caregiver and the challenges that come with it can help relieve stress. Staying in contact with other family members and keeping them updated on their loved ones allows them to step in and support when needed.

Making Your Health A Priority

Caregivers, along with the patient, must make sure their health is a priority. Without the caregiver in good health, they wouldn’t be able to provide the optimum care the patient needs. Along with regular check-ups, making sure you get yearly Flu shots, testing, and staying active is important. Being a caregiver can be physically demanding, and your health is just as important as the Alzheimer’s patient’s health.

Participate in Research for Alzheimer’s

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, but there are clinical studies that the patient and caregiver can participate in. Since the caregiver needs to assist the patient with all that comes with being in a study, both the caregiver and the patient would receive a stipend. The more participants in Alzheimer’s studies, the more research is done, getting us closer to a cure! For more information on our currently enrolling Alzheimer’s disease studies, give our office a call.

Can a type of seaweed really be used to treat Alzheimer’s disease? Some scientists think so, and it’s even being tested in clinical trials today. Oligomannate is extracted from seaweed and can be used as a potential therapy for Alzheimer’s. It is being developed by Shanghai Green Valley Pharmaceuticals and has been given conditional approval by China. Oligomannate is in clinical trials in the U.S., Europe, and other countries, pending approval. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that worsens over time and is the most common form of dementia. Amyloid plaques and tau tangles are widespread in Alzheimer’s and physically change the brain. Neurons die over the course of the illness, and neural networks become sparsely connected. This leads to the atrophy, or wasting away, of brain matter. This is a visible, significant loss of brain volume. So how does Oligomannate work to stop these proteins from forming plaque? In the preclinical studies, oligomannate was able to decrease the build-up of beta-amyloid protein in the brain, which in turn can improve cognitive function. Furthermore, oligomannate may be able to regulate the connection between microbiomes from the gut to the brain, reduce harmful metabolites produced by these microbiomes, and lessen inflammation. All of which help to reduce the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. More research needs to be done before it is FDA-approved in the US. Want to play a part in finding a possible treatment for one of the most devastating diseases? Consider participating in a research study! To see what is enrolling, visit our enrolling studies page. Your help is needed to move medicine forward. Source: Alzheimer’s News Today

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder that was first described in 1906 by Dr. Alois Alzheimer. Since that time, Alzheimer’s disease has become the most common cause of dementia (accounting for 60-80% of cases). It is estimated that in 2016, 5.4 million American’s of all ages have Alzheimer’s disease. One in nine people age 65 and older has Alzheimer’s. JCCR has participated as a research center in clinical trials over the past several years to limit the devastating consequences of this difficult to treat disease.

The number of American’s with Alzheimer’s is anticipated to escalate rapidly with the aging of our population, with estimates ranging from 13.8 million to 16 million by 2050. This estimate assumes no medical breakthroughs to prevent or cure the disease.

Alzheimer’s is a slowly progressive brain disease that begins well before clinical symptoms emerge. The persistent accumulation of abnormal proteins in the brain lead to death of brain cells over time, which causes decline in cognitive function. Thus, a significant amount of protein accumulates in the brain over many years before a sufficient amount of brain injury has occurred to cause symptoms noticed by the patient or family/friends.

The medications currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s temporarily improve symptoms by increasing the amount of specific neurotransmitters in the brain. However, they do not address the accumulation of abnormal proteins or brain cell injury and, thus, do not treat the underlying cause of the disease. The first medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer’s was donepezil in 1996. The last was memantine in 2003. There have been no new/novel treatments approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer’s since 2003. From 2002-2012, 244 drugs for Alzheimer’s were tested in clinical trials, and only one went on to receive FDA approval.

Currently, a worldwide quest is underway to find new treatments to stop, slow or even prevent Alzheimer’s. The last 10-years have seen tremendous growth in research on early detection, and researchers believe that early detection will be key in preventing, slowing and stopping the disease. There is a new wave of optimism in the scientific community about Alzheimer’s treatments.

As eloquently stated by Bill Thies, PhD, Senior Scientist in Residence with the Alzheimer’s Association: “Despite increasing momentum in Alzheimer’s research, we still have two main obstacles to overcome. First, we need volunteers for clinical trials. Volunteering to participate in a study is one of the greatest ways someone can help move Alzheimer’s research forward. Second, we need a significant increase in federal research funding. Investing in research now will cost our nation far less than the cost of care for the rising number of Americans who will be affected by Alzheimer’s in the coming decades.”

Here at JCCR, we understand the importance of recognizing cognitive decline and identifying Alzheimer’s in its early stages. Recent scientific breakthroughs provide hope that new treatments can prevent accumulation of abnormal proteins in the brain and markedly slow the disease. We want to help individuals and their healthcare providers identify the early signs of memory changes so that effective interventions can be initiated promptly. We want to help individuals maintain their memory function and their independence. We also want to facilitate participation in clinical trials that will help our understanding of memory disorders and lead to treatments that will help maintain memory function. We look forward to working with you and your healthcare providers.

Erin G. Doty, MD

Neurologist, Board Certified

Memory issues occur commonly and when they begin, one may worry about the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. While Alzheimer’s may cause memory loss, memory loss is also a symptom of many reversible conditions. Early memory testing is crucial to determine the cause of memory loss to help reverse it before it becomes permanent.

For example, certain over-the-counter medications have been associated with dementia. A recent study came out this month linking Benadryl to dementia. Benadryl has many uses, including allergy symptom relief. The active ingredient in Benadryl is diphenhydramine. This drug blocks the action of acetylcholine (anticholinergic effect) and is used as a sedative because it causes drowsiness. 1 Diphenhydramine is used in most over-the-counter sleeping pills, for motion sickness, and other allergy medications.

A study completed in 2015 at the University of Washington showed the longer and more consistently people took anticholinergics, the more likely they were to develop dementia. Other drugs that contain anticholinergics are used to treat diseases like asthma, incontinence, gastrointestinal cramps, and muscular spasms. They are also prescribed for depression and sleep disorders. 2

While we do not fully understand dementia, we do know that the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is important in brain processing and memory. We know that the acteylcholinesterase inhibitors (drugs like Aricept (donepezil), Exelon (rivastigmine) and Razadyne (galantamine) which inhibit the breakdown of acetylcholine, do provide symptomatic improvement in affected patients.

It would seem that taking a combination of acetylcholinesterase (cholinergic) with an anticholinergic drug (such as Benadryl) is probably not a good idea. In fact a recent study showed 16% of Alzheimer’s patients living independently were doing just that.

This 2015 study is backed up by another study that came out this month offering the most definitive proof yet, that anticholinergic drugs are linked with cognitive impairment and increased risk of dementia. Using brain imaging they found that patients taking anticholinergic drugs indeed had lower metabolisms and reduced brain sizes.

The bottom line is that given all the research evidence, you should be aware that these over-the-counter medicines may reduce the effectiveness of your prescription medicines. If you or a loved is worried about memory loss, the first step is to get tested to see if it’s from a treatable or reversible cause. Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research offers a professional memory screening for no cost to you. Make an appointment today to help put your mind at ease.

1- https://www.medicinenet.com

2- https://www.healthline.com